You Get What You Incentivize (Newsletter 016)

Greetings friends.

I suppose I should be thankful for the West's gradual drift toward socialism. Why, you ask? Not for any political or financial reason. No, simply because the questions being asked by society about the role of wealth and wealth creation caused me to ask those same questions of myself. And I am living proof that people respond to incentives. Let me explain.

Western countries need more money than ever. This comes by virtue of steadily expanding the welfare state, together with increased expectations about what minimum standards of living all citizens deserve to maintain their dignity. And because politicians like to get re-elected, they don't like telling voters they will have to pay for all those benefits. Thus it is we have witnessed the public vilification of "millionaires and billionaires" who refuse to pay their "fair share" of taxes to fund society's necessary programs. See pretty much any public statement on this topic by politicians at the far ends of the generational spectrum spanned by Bernie Sanders at one end and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez at the other.

Last week I wrote about the tremendous benefit we all get in society when individuals act in ways that benefit others. See How Does It Benefit Me? When we agree to take part in society, we agree not only to limit our individual freedom, but also to contribute to society in the form of taxes. I believe very strongly in the social contract that we all implicitly have entered. As a result, for my entire working life I could easily justify paying what seemed to me sometimes very significant amounts of money in taxes.

With federal and local income taxes, unemployment and various social security taxes, and property and wealth taxes, most years I paid something like half of my total income in taxes between Switzerland and the United States. Sure, this was a lot of money, but I was making a direct contribution to society, and it was a great feeling to know that politicians and citizens appreciated the taxes my hard work generated.

Imagine then my dismay to hear that in fact I was a "fat cat" who was not only not a productive member of society, but a systemic oppressor. That my income was the result of stealing from those less fortunate. That I was neither hard-working nor deserving, but only a lucky elite clinging to undeserved power. And worst of all, that despite my untold advantages, I was refusing to pay my "fair share" in the ultimate act of pure greed and selfishness.

That didn't feel so good. It certainly wasn't consistent with how I felt about myself, but maybe I was wrong. Maybe I had been oppressing other, more deserving, people all this time. That my actions would have been unknowing and certainly undesired seems a weak excuse. In my case, the direct result of telling me I was a villain for being successful was to cause me to question what success was. I came to see the wisdom in the Stoic idea that success and happiness should not be measured in money or possessions but in self-possession.

If success in terms of wealth creation is undesirable because it is inevitably the result of oppression, I don't want any part of it. So I decided to leave the path of wealth behind. I gave up my high-powered job, reduced my hours, and ultimately quit working in my old profession altogether. I have embraced the idea that I don't need material possessions to be happy, and that indeed the relentless pursuit of more is what drives so many to dissatisfied distraction.

I discuss this in Moral Letter 031 On The Value Of Work. If you have thought carefully about the relative importance of things, then you owe it to yourself to make sure your actions are consistent with your thoughts. I would rather be a valued member of society, contributing something society wants. For example, my inspiration for Klugne.com was to share thoughts on how to live a better life in the hope that it actually helps people do so.

I also revisit the importance of working out for yourself what success means in the next installment of the Stoic career articles. This week's contribution is These Things May Be Hurting Your Career. This contains a list of things you may be doing that may be inadvertently preventing you from achieving your goals.

So far so good. And yet. I admit to having one niggling doubt running around my head. This relates to my having studied economics at university, and being concerned about what the future holds for our countries. Because my own needs are slight, with my savings I am today self-sufficient. Aside from the great benefit of living in a free society itself, I am taking no payments or benefits from society. But that is not the case for most citizens.

According to testimony from the Tax Foundation before Congress in March, even before the pandemic fully 60 percent of American households received more in direct governmental benefits than they paid in federal taxes. Where does the money to pay for all this come from? Given the headlines, you may be shocked to learn that the U.S. has the most progressive income tax system of any industrialized country. A progressive tax just means that as a person's income goes up, their tax rate goes up even more.

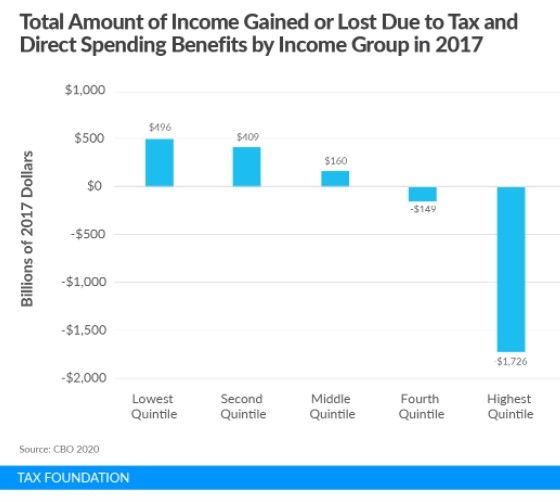

In 2018, the top 1% earned 20% of income, but paid 40% of the taxes. Pity the top 0.1% of taxpayers, who paid more in taxes than the bottom 75% of taxpayers combined. According to the Congressional Budget Office, in 2017 the bottom 60% of American households collectively received more than $1 trillion more in direct governmental benefits than they paid in all federal taxes. The top 20% paid $1.7 trillion more in taxes than they received in direct benefits:

It seems like the taxes paid by the highest earners go directly to funding benefits for everyone else. And not only that, the taxes paid by the rich are fundamentally important. Or as the Tax Foundation puts it in their conclusion:

Digging through the data, it is difficult to find evidence that the U.S. tax code is rigged in favor of the rich and corporations. The wealthy’s share of the income tax burden has never been higher, redistribution from them has never been greater, and more than 53 million low- and middle-income Americans pay no income taxes because of the generous credits and deductions benefiting them.

Here's what I conclude from all this. If your appetite is unlimited, no amount will ever be sufficient to satisfy your wants. No amount of tax is "fair" when there is no limit on what you aim to spend and redistribute.

But I can think of something that does have limits: the appetite of good-willed people to work for the benefit of others who don't acknowledge or appreciate it. It seems reckless to not only take almost half a person's earnings, but in the bargain tell them that they are somehow morally bankrupt for not giving more. Don't be surprised when they decide to change course in response to what you are doing and saying.

This makes me concerned for the future of our society. When citizens do not see and value the contributions that other individuals make, we weaken the bonds of the social contract that hold us together. It is risky to see how much further we can weaken these bonds before something gives way.

Much of the stress can be traced back to our unbridled consumption, and the thinking that we need to give people material goods for them to achieve happiness. Besides taking ever-greater amounts from an ever-smaller group of people who are actually paying taxes, we are also running up gigantic debts. This comes from borrowing to spend money even beyond the massive amounts we already tax and redistribute.

I've written before about the dangers inherent in the ballooning national debt. See Pull The Emergency (Debt) Brake. The key message is that small steps taken over time can add up to big effects. This mechanism works both in the direction of making things worse and making them better. I discuss the power of continuous improvement in this week's Moral Letter 032 On Continuous Improvement.

One of the things I admire most about a society is whether it has the ability to make and successfully implement long-term plans. That is, can it decide to forego a current benefit to achieve a future objective? For example, can society agree to pay an incrementally higher amount in taxes for decades to fund an expensive, but important infrastructure project? I've seen countries do this, and it is exceptionally powerful. It takes a common will to act selflessly for the benefit of future generations. Now you know why I so bemoan the loss of altruistic-like behavior.

The way for us to curb excessive spending and massive debt is gradually. Use the power of time to chip away at what today seems insurmountable. First reduce deficit spending to zero, and then start to run a small surplus. Then maintain and wait until the problem takes care of itself.

Some of you will say you think this is impossible. To those I ask, what do you think is the alternative?

Be well.

Member discussion