Pull The Emergency (Debt) Brake

If you are speeding out of control, shouldn’t you consider pulling the emergency brake?

Twenty years ago, the Swiss voted overwhelmingly to adopt a constitutional amendment implementing a so-called “debt brake.” The basic rule is that government expenditures may not exceed receipts over an economic cycle. See Debt Brake for a good overview of the system in English. Data and certain tables below are taken from the Debt Brake Fact Sheet.

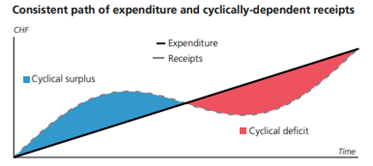

The Swiss system has an adjustment mechanism that takes into account the economic environment: when the economy is doing well, the expenditure ceiling is lower than receipts, so Switzerland generates a surplus. When the economy is in recession, however, the system tolerates deficit spending.

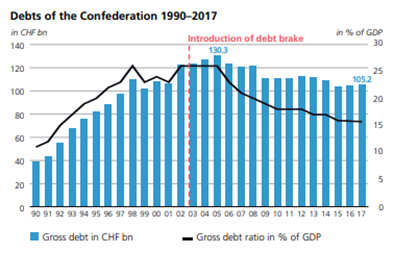

Although Switzerland adopted the debt brake in response to rapidly rising public debt in the 1990s, it carried relatively low indebtedness compared to other countries. One common way to evaluate how significant a country’s debt load is compares the debt to the country’s total economic output, or Gross Domestic Product. Switzerland’s ratio of debt to GDP peaked at around 25%. Nonetheless, the rate at which Switzerland’s debt was rising led to worry about where this would lead if left unchecked.

The theory behind the rule was to help ensure the sustainability of public finances (no more uncontrolled growth in debt) while also smoothing economic cycle fluctuations. So how well has the debt brake functioned in practice? Since the introduction of the debt brake, both the absolute amount of indebtedness and the ratio of debt to GDP have steadily declined.

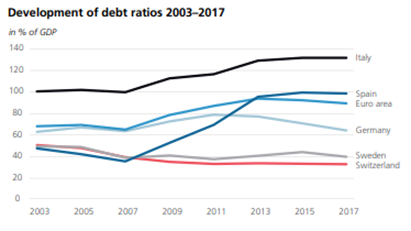

Ten years after Switzerland adopted the debt brake, the sovereign debt crisis in Europe led several EU member states to undertake to adopt their own debt brakes at the constitutional level. For example, Germany introduced a debt brake in 2011 based largely on the Swiss model. This has had a beneficial effect on the development of Germany’s debt to GDP ratio as well.

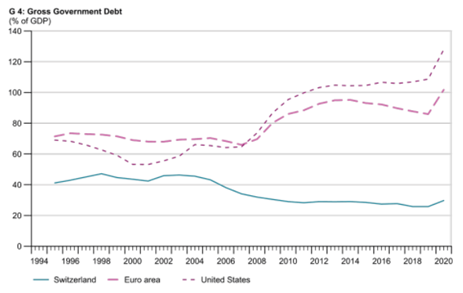

But how does it work in a real crisis, like the coronavirus pandemic? As expected, due to the economic downturn caused by COVID-19, the Swiss government incurred higher spending in 2020. Switzerland’s debt to GDP ratio increased by about 3 percentage points. This compares with expected increases of 16 percentage points in the Euro area and 19 percentage points in the United States.

By operating the debt brake for almost twenty years, Switzerland started from a much healthier position when the pandemic struck. Further, by drawing upon surpluses accumulated in prior years, Switzerland was able to support the economy in the downturn with a much lower growth in its debt to GDP ratio.

These results demonstrate the power of continuous improvement: small changes made steadily over time can add up to a big impact.

The problems the U.S. faces with both its regular deficit spending and its expanding debt to GDP ratio are serious but solvable. Waiting until disaster strikes would mean the remedy would be that much more painful: think Greece or Venezuela.

Our representatives in Congress have introduced so-called Balanced Budget Amendments on multiple occasions, most recently in February 2021: Senators Introduce Balanced Budget Amendment. These have similar aims as the European debt brakes, and would operate in a similar fashion. Advocacy relating to these Balanced Budget Amendments, however, has typically stayed in the realm of the hypothetical, where opponents speculate a range of undesirable outcomes that might occur. Constitutional Balanced Budget Amendment Poses Serious Risks

But rather than guessing about the impact of debt brakes, the United States can look to the actual experience of other developed economies in designing an appropriate system for the U.S.

Starting now with the simple step of not spending more than we take in would put the United States on a path to healing its public finances. If we adopt a flexible system like Switzerland’s, we can also build up reserves to help smooth the impact of cyclical shocks to the economy.

It’s not too late to tap on the brakes, even if we don’t pull the emergency brake. See Failing the Marshmallow Test and The United States is Not Bankrupt … Yet.

Be well.

Member discussion