029 - On Easy Lessons - Moral Letters for Modern Times

You have mentioned to me twice now that the study of philosophy is out of vogue for most people, and that the written word is so antique as to be virtually forgotten. If we are not on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram, or better yet posting a weekly Spotify podcast or YouTube video, then we might as well put on our orthopedic shoes and sweater vest and spend the afternoons playing Bingo at the senior home.

Everywhere we turn, we are confronted with the incredible shrinking attention span. Who has the time to read entire books when Blinkist can give you the gist in a blink? Why watch a movie in a theater when you can stream 30-minute episodes on any device wherever you are? And who has thirty minutes to watch a full episode, when fifteen second diversions are available nonstop at the flick of a finger? You can scarcely finish a thought before the mind has wandered, flitting about like a hummingbird on the non-stop search for nectar.

“In such an environment,” you say, “surely it is folly to expect to find an attentive audience willing to sit and do the hard work of reading and thinking. Hadn’t we best adapt our message for the audience’s abilities?” It’s true, we could chew our message to cud and spit it out for a slack-jawed crowd to mindlessly slurp. Though we would surely extend our reach to the broadest audience in this way, my dear Deuteros, we would also dilute our message until it lost its meaning. Do you teach an athlete to run a marathon by strolling around the block? Or to lift a great weight by putting feathers on one’s forearms? No, and nor do we train the mind when we give it such light fare. Little effort means little progress. It is ruminating on deep thoughts that generates growth, not consuming half-digested musings.

I don’t suppose the glitterati will let this challenge go unanswered. They will pile up the charges against us, and make the case thusly: “If you can’t express your ideas simply in ways an average person can understand, you don’t understand them yourself.” This we may hear from a Hollywood starlet whose claim to fame is a nub nose and a symmetrical face that is as much the result of gifted plastic surgery as genetics. I can see why they prefer the simpleton’s version, but the arrows they shoot at us never hit their mark, because they cannot hit what they do not know to aim at.

Our critics do not surrender, but rather they turn their weapons on our audience: “The Stoics’ medicine is bitter, and their course of recovery long and hard. Come to our side, and we will make everything easy for you: the one-hour work day, the no-discipline diet, and the no-sacrifice path to success!” This is appealing fare, no doubt, and it will attract the masses as surely as it fails to nourish them. The only guarantee the consumer of such light sustenance can be sure of is that another snack will be available for purchase just as soon as this one disappears from your monthly credit card statement.

Deep down, Deuteros, do we not know when we are being sold nostrums and snake oil? We are willing dupes in being dazzled by packaging, bamboozled by dust-jacked blurbs. Show me a popular self-help author, and I will show you someone who has chosen to sell surface appeal instead of depth, and platitudes over purpose. The greater the renown among the public, the less likely you are to have served before you gourmet food. For the masses want cheap and tasty meals, and you deliver these in quantity by following mass-production principles.

There is one type of reading that I give you my blessing, indeed my urging, to avoid at all costs: that is self-help books of almost any kind. “What?” you wonder. “Am I to discard the advice of experts altogether? And how ironic that you who are so keen on dispensing wisdom forbid my seeking it from others.” What we are discussing in these letters, my dear Deuteros, are truths and wisdoms that belong to no expert, but are the common good of mankind. Furthermore, we are picking them up not as finished goods, but must adapt, amend, and apply our lessons in a personal context.

Your self-help expert generally comes in one of two flavors: the scholar who has studied tables of figures until they tease or torture out statistical significance, and the business executive who explains their success in hindsight and with a healthy dose of selective memory. As to the first, whether squeezed between unprovable hypotheses and the repeatability crisis, you are likely as well served by consulting your palm reader as you are the academic under pressure to publish. And as to expecting the average executive to have sufficient self-reflection to understand the role factors beyond luck played in their fortune, let’s just say you will get as useful advice from the one who explains how they picked the numbers for the winning lottery ticket.

In freeing you of this burden, I have greatly eased your load, for there are now whole aisles in the bookstore you may profitably avoid. In return, I ask you to stop and consider this:

Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect.

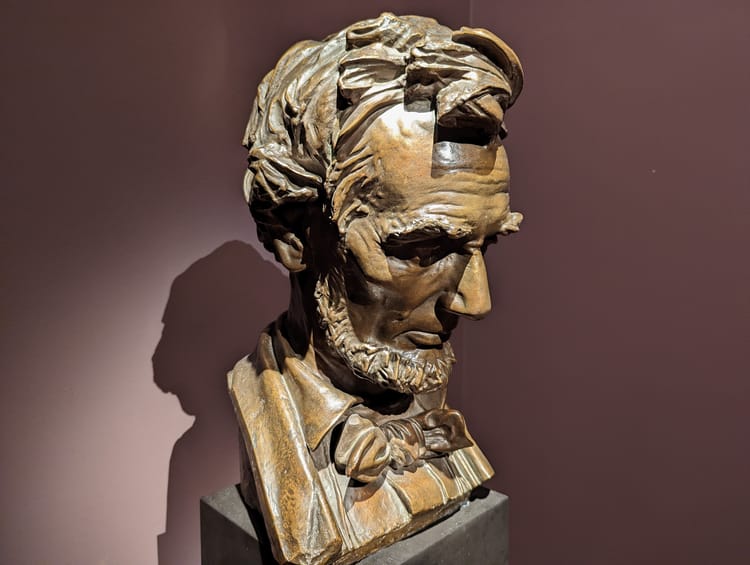

The majority is often not wrong, of course, but they are not right just by virtue of being many. “What philosopher uttered these words?” you ask. It was the American humorist and fantabulist Mark Twain. Having long catered to the masses in aid of keeping his coffers stocked, the man also known as Samuel Clemens in his private time knew well this lesson: that to reach the greatest audience you must appeal to the least common denominator. Better that we count our students on one hand than we sell out our principles for profit.

Be well.

Member discussion