Pity the Doomed Backers of Biden’s Campaign

Greetings friends and fellow thinkers!

Two psychological principles explain why otherwise smart and accomplished people make poor decisions: The sunk cost fallacy and the consistency principle.

In lay terms, we hate acknowledging we’ve made a mistake and we like to think of ourselves as logically consistent individuals over time. Taken together, the two principles create powerful incentives for self-defeating behavior.

We can see both playing out among wealthy donors who continued to back ailing President Biden’s campaign before he finally withdrew under duress. Just because we can easily see how these donors’ poor decisions were equivalent to throwing a lit match on a stack of gasoline-soaked bills, it is risky to assume we would avoid a similar fate.

I’ll describe the risks and give you my suggestions for fortifying yourself from falling into the trap.

Billionaires are people, too

Although I know some here disagree, I believe many billionaires succeed because they’re smart and skilled. I was thus all the more surprised when observing wealthy backers of Biden’s campaign making further contributions after his public collapse in the presidential debate.

Then I remembered my psychology training and that billionaires are humans, just like us. That means they are subject to the peccadillos that haunt our everyday thinking and decision-making.

To illustrate, consider what happens when we contribute to a cause.

Spending money on a cause comes with strings attached

You would think that making a small donation to a cause carries little risk. If you value your independence, however, psychology tells us to be careful indeed before handing over a penny.

That initial, insignificant payment represents much more than money — it is a statement that you support the cause. “So what,” you might be thinking. “I do support the cause. What’s the harm in saying so?”

The harm comes from your inherent desire to see yourself as a logical, consistent person. Thus, when the organization you donated to requests a second donation (and a third and a fourth, etc.), you face a quandary.

- Your initial donation proves you do support the cause. What does it mean if you refuse a second donation?

- Does it mean you are an unreliable person? That you don’t know your own mind?

- Did you change your mind? What changed in the meantime to cause it?

These thoughts run through our heads largely unnoticed. But they still create unwanted stress. Many people respond to the uncertainty by going along with the second request.

Even if a person feels mild discomfort at paying more, it’s easily overcome by avoiding the discomfort arising from questioning their nature. A person can also tell themselves they are virtuous and so become even more wedded to the cause. All without having made any conscious decision to adopt a new cause.

Small donation requests are a tactic meant to manipulate us

Psychologists have reported such findings with naivete about the implications. Sure, it’s interesting to understand the quirks of human thinking. But it’s much more valuable to people who want to leverage those quirks against us.

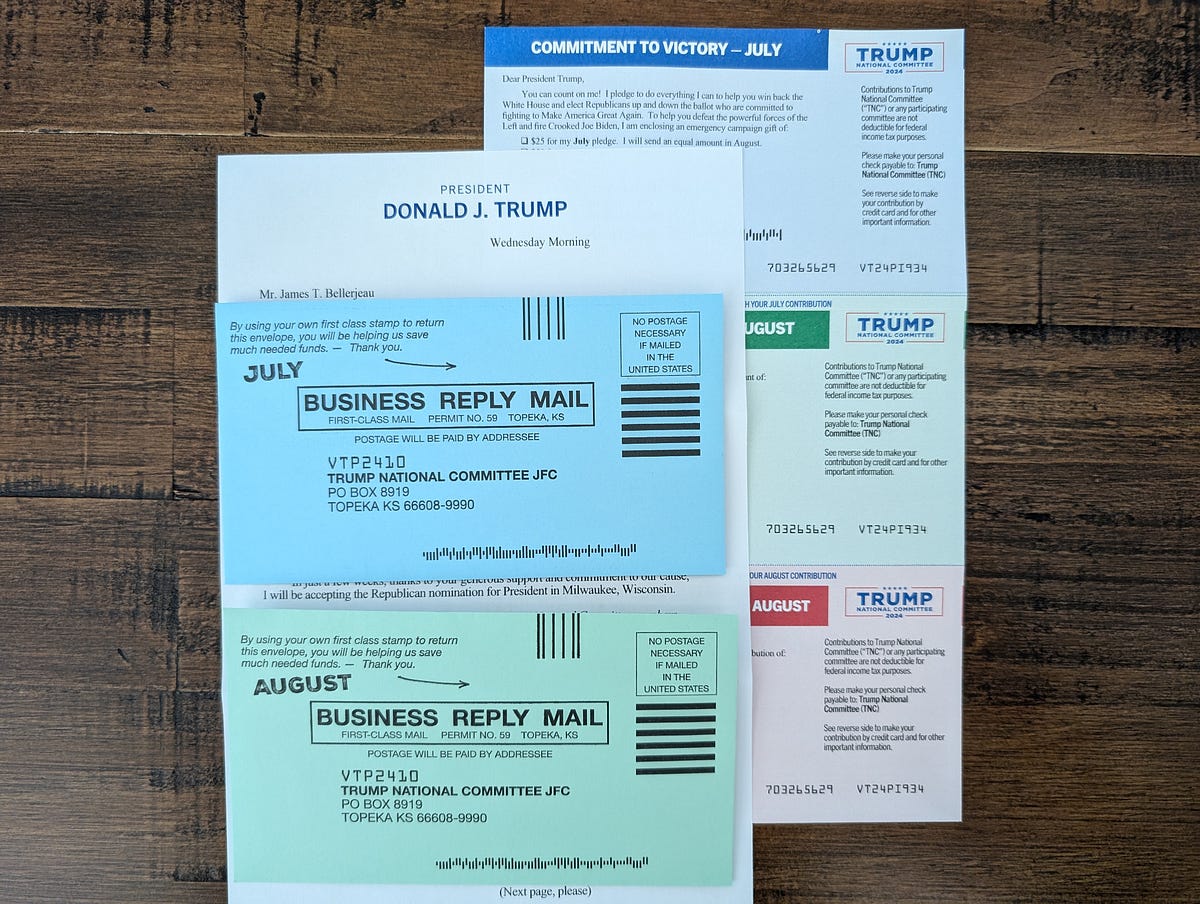

The day after the presidential debate, my mailbox was flooded with donation requests from both campaigns. They ask for a seemingly minor contribution to confront the obvious threat to democracy, stability, and the future of all we hold dear.

I know, though, and now you do as well, that there’s no such thing as a minor contribution. The potential cost to your independence is high.

Moreover, the psychological risk increases as the contribution increases.

Donating big bucks seriously puts your self-image on the line

Donating a few dollars probably doesn’t seem like a major life event, even though I just warned you that doing so will predictably influence your future behavior.

Now imagine what it feels like to donate $1 million, $10 million, $100 million or more to a cause. That’s saying something about you and what you believe, isn’t it?

Imagine further that your huge donation was to a cause revealed to the entire world as fundamentally flawed. That is deeply distressing. It raises the concern that you, of all people, do not know how to make good decisions.

We are so keen to avoid being considered fools that we will often double down on our earlier commitment. We will tell ourselves any lie necessary to make our past actions sensible. This explains the spectacle of top donors in the days following the debate:

- Comparing President Biden to Yoda, old and frail yet wise

- Pointing out that Warren Buffet made a great deal of his fortune in the last ten years in his 80s and 90s

- Suggesting that, despite the obvious physical decline, his mental state is still strong

The irony is that to avoid the psychological pain of being considered foolish, individuals will say things like this that remove all doubt. They are blind to the trap they’re in. Their flailing only binds them more securely.

It’s an alarming spectacle, but one we can learn from.

Protect your psyche by avoiding public commitments

If someone asks you to make a public statement, be aware that the seemingly harmless request is anything but. Doing so will trigger your largely unconscious desire for internal consistency.

- When the waiter asks you, “How is everything?” not thirty seconds after delivering your food, now you know it’s a trick. By getting you to say “Everything’s fine” before you’ve had a chance to take a bite, they reduce the odds you’ll feel comfortable complaining later.

- If you ever, in a moment of weakness, agree to round up your purchase at the grocery store in aid of some mumbled charity, you have been tricked. You’re much more likely to do so in the future because you’re the sort of person who says yes to such requests.

- If you register with a political party, you can say farewell to a portion of your independence and critical thinking.

- If you contribute to a cause, you can expect to feel inexplicable pressure to do so again.

I trust you get the point: The only way to preserve your independence in the face of people who would steal it from you is to jealously guard yourself from making public commitments.

To use the above examples:

— Tell the waiter, “We haven’t had a chance to try everything yet. We’ll let you know.”

— Tell the cashier, “Oh, I make my charitable contributions separately.”

— Do not register for membership in a political party.

— And only contribute to causes you have consciously selected as worth your ongoing time and attention.

Not everyone promoting a “good cause” has your best interests in mind. Now you are forewarned. I hope you also feel a bit forearmed.

Be well.

I’d be happy if you read more of my stories and it’s no trick. My goal is to help you help yourself in a world where most people are merely helping themselves.

Member discussion