Speeding Out of Control –Time to Pull the Brake?

Greetings friends!

If you’re feeling fatalistic about America’s national debt, I’ve got good news for you. (And no, it’s not to embrace that we’ll take the world down with us if we go. That is one clever approach to living with our debt, however.)

It’s that we could solve our debt problems the same way we got into them: gradually over time. All it would require is taking away the blank check that Washington believes Americans have given it.

Regular readers will forgive me for using Switzerland as our role model in how we can do better.

Switzerland adopts a debt brake

Twenty years ago, the Swiss voted overwhelmingly to adopt a constitutional amendment implementing a so-called “debt brake.”

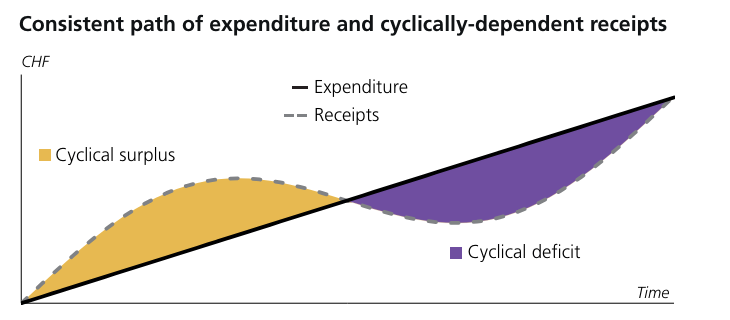

The basic rule is that government expenditures may not exceed receipts over an economic cycle. See Debt Brake for a good overview of the system in English. Data and certain tables below are taken from the Debt Brake Fact Sheet linked there.

The Swiss system has an adjustment mechanism that takes into account the economic environment: When the economy is doing well, the expenditure ceiling is lower than receipts, so Switzerland generates a surplus. When the economy is in recession, however, the system tolerates deficit spending.

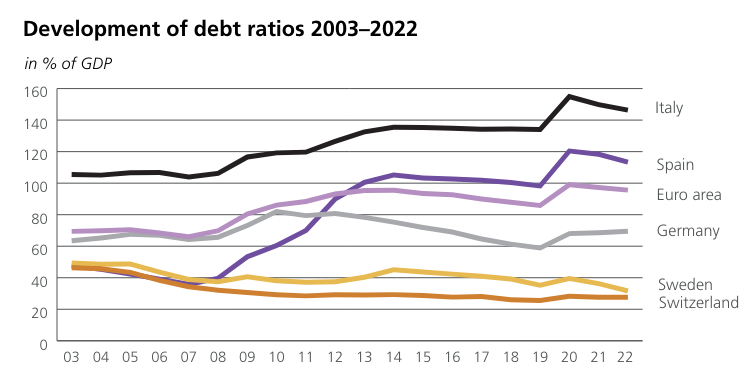

Although Switzerland adopted the debt brake in response to rapidly rising public debt in the 1990s, it carried relatively low indebtedness compared to other countries.

A common way to evaluate how significant is a country’s debt load compares the debt to the country’s total economic output or Gross Domestic Product.

- At the time, Switzerland’s debt-to-GDP ratio was around 25%.

- Nonetheless, the rate at which Switzerland’s debt was rising led to worry about where this would lead if left unchecked.

- I invite you to pause and consider the previous sentence.

The theory behind the rule was to help ensure the sustainability of public finances (no more uncontrolled growth in debt) while also smoothing economic cycle fluctuations.

Switzerland uses the debt brake

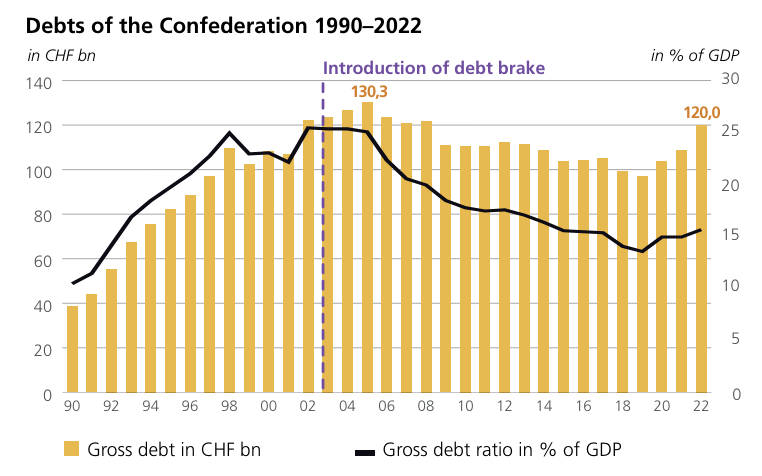

So how well has the debt brake worked? Since adopting the debt brake, Switzerand’s absolute indebtedness and its debt-to-GDP ratio have steadily declined… until the pandemic. More on that in a moment.

Other countries jump on the bandwagon

Ten years after Switzerland adopted the debt brake, the sovereign debt crisis in Europe led several EU member states to adopt their own debt brakes at the constitutional level.

For example, Germany introduced a debt brake in 2011 based largely on the Swiss model. This has had a beneficial effect on the development of Germany’s debt-to-GDP ratio as well.

These results demonstrate the power of continuous improvement: Small changes made steadily over time can add up to a big impact.

How did the debt brake work during the pandemic?

The real test is how well the debt brake works in a crisis, like the pandemic. Due to the economic downturn caused by COVID-19, the Swiss government spent significantly more in the pandemic years and incurred much higher debt.

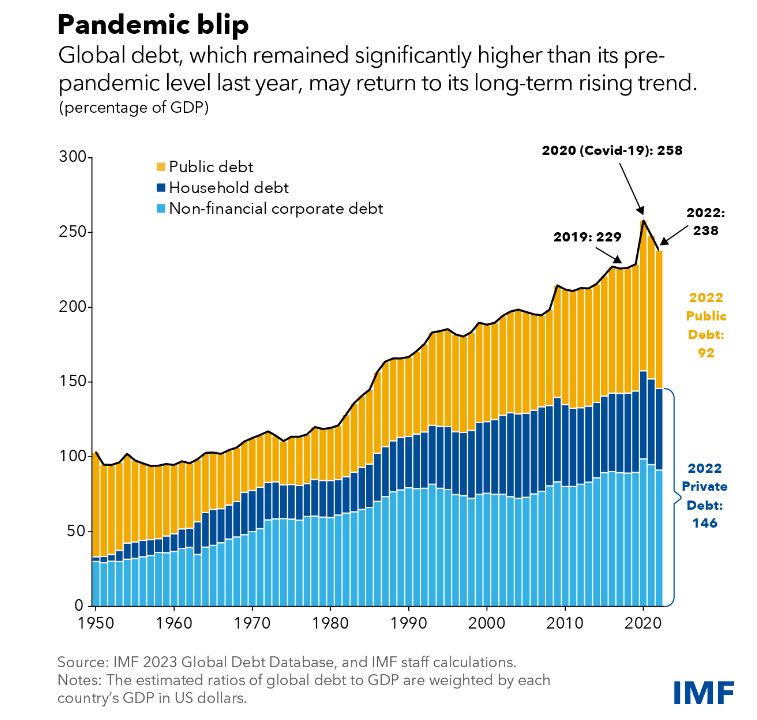

Switzerland’s debt-to-GDP ratio increased by about six percentage points over the last three years. This compares favorably with the global increase in debt-to-GDP of fully 35%. That spike is evident in the chart above comparing European debt ratios.

By operating the debt brake for twenty years, Switzerland started from a much healthier position when the pandemic struck. Further, by drawing upon surpluses accumulated in prior years, Switzerland supported its economy in the downturn with much lower growth in its debt-to-GDP ratio.

This chart gives the global contrast:

What about the United States? Are we doomed?

The problems the U.S. faces with both its regular deficit spending and its expanding debt-to-GDP ratio are serious but solvable. Waiting until disaster strikes would mean the remedy would be that much more painful: Think Greece or Venezuela.

Our representatives in Congress have introduced so-called Balanced Budget Amendments on multiple occasions, including in February 2021. These have similar aims as the European debt brakes and would operate in a similar fashion.

Advocacy relating to these Balanced Budget Amendments, however, has typically stayed in the realm of the hypothetical, where opponents speculate a range of undesirable outcomes that might occur.

But rather than guessing about the hypothetical impact of debt brakes, the United States can look to the actual experience of several other developed economies in designing an appropriate system for the U.S.

Starting now with the simple step of not spending more than we take in would put the United States on a path to healing its public finances. See Failing the Marshmallow Test, Over and Over.

If we adopted a flexible system like Switzerland’s, we could also build up reserves to help smooth the impact of cyclical shocks on the economy.

It’s not too late to tap on the brakes, even if we don’t pull the emergency brake.

Be well.

If you want to keep building your own surplus of great ideas, subscribe to read my stories.

Member discussion