Failing the Marshmallow Test, Over and Over

Greetings friends!

Can you hold off enjoying an immediate pleasure in the hope of getting a future benefit?

Can you set aside that slice of cake for dessert to maintain a healthy weight? Will you work up the will to work out when you’re tired to build your fitness?

Imagine how you’d feel about a much simpler task: choosing between eating a single marshmallow now or getting two marshmallows in 15 minutes.

That was the choice facing young children in a Stanford University experiment in the 1970s. When checking back in with the children over their lives, researchers noticed something interesting:

- Children who had successfully delayed gratification by waiting for the reward had higher achievement later in life.

- They outperformed in diverse areas such as better social skills and higher SAT scores, and were more able to cope with stress.

See The Bing “Marshmallow Studies”.

Later studies revealed that children will delay gratification longest when they trust the future reward will be forthcoming. If they are uncertain about the reward, they give in to temptation earlier.

The marshmallow test explains what’s wrong with America.

We’re failing the marshmallow test as individuals

Americans are failing the marshmallow test at an individual level. Consider how we behave with our spending. U.S. household debt at the end of 2023 was $17.5 trillion (American Household Credit Card Debt Statistics):

- We owe over $12 trillion in mortgage debt, spent buying ever bigger houses. The average size of a family home has increased by more than 60% since the 1970s. New US homes today are 1,000 square feet larger

- We owe almost $1.7 trillion in student loans (despite epic loan forgiveness by politicians buying votes), an amount that has grown by more than 600% since 2003. Student Loan Debt by Year

- We have binged on another $3 trillion or so in auto loans and credit card debt.

We’re failing the marshmallow test as a nation

With this behavior on an individual level, is it any surprise that America is also failing the marshmallow test at a national level? Our national debt in May 2024 was over $34 trillion (U.S. National Debt Clock):

- We are spending money we don’t have to fund immediate consumption we often don’t need and so running up trillion-dollar annual budget deficits. We are consequently building up our national indebtedness to levels never seen by any nation in world history.

- We watch our basic infrastructure (highways, utilities, schools) crumble around us, seemingly unable to halt the decay. By neglecting even preventative maintenance in the short term, we are courting much larger costs to replace worn-out facilities when they fail.

Why can’t we manage to delay gratification?

The dynamics of delayed gratification help explain why as individuals and as a nation we spend beyond our means.

- Consumption today is worth more than consumption tomorrow. Put another way, money in the future is worth less to us than money today.

- Similarly, costs in the future hurt less than costs today, and we thus prefer to pay costs as late as possible. A debt repayment deferred to next year is preferable to one we must pay today.

Now imagine how we feel about racking up costs today for a bill that might never come due. Or even if the bill must eventually be paid, that someone else will have to pay it?

You might well conclude that present consumption is worth more than speculative future costs. We are certainly behaving as if this were true.

We spend more because we have more

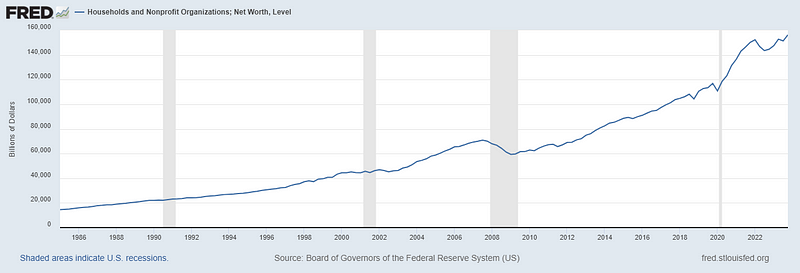

Although Americans’ levels of individual indebtedness have been rising dramatically, our net worth has also been increasing. Americans’ net worth considerably exceeds the amount of our indebtedness. (See Household Net Worth Level.)

When the value of people’s assets rises, they spend more, a phenomenon known as the wealth effect. American households have been experiencing a dramatic growth in net worth. So yes, we’re spending more than ever, but at least by this metric, we’re not less well off.

Keep in mind, though, that you can have significant assets and still run into trouble if you can’t pay your debts from the current cash flow. Lehman Brothers had almost $700 billion of assets when it filed for bankruptcy in 2008. The problem is rather one of liquidity (more on this below).

Our national debt is a national shame

Whenever existing debt comes due, we just issue new debt to pay off the old, plus whatever new debt we need to fund current spending. It’s as if we have a credit card that not only requires no minimum payment each month but has no limit! We can spend whatever we want for as long as we want.

While this is a pleasant daydream, do we really think the world will keep lending us money without limit?

As we roll over existing debt and steadily add to our balance, we can expect worried lenders to demand ever-increasing premiums. They will want more interest to cover the growing risk that we default on our debt or, more likely, inflate our currency by printing money, thereby devaluing it.

An honest person will admit that there must come a point at which either our credit or our currency is ruined, or both.

Watch out for liquidity problems

The value of our land, homes, and factories may be significant. But if we can’t make an interest payment because cash flow is lacking, we may find our creditors forcing sales of our assets to generate cash.

Suddenly the value of our assets comes under pressure because in a forced sale, buyers know they have leverage.

If we continue to spend more than we earn, eventually we will find that we need to sell assets to generate cash flow. That will start a rapid cycle of declining net worth.

Depending on how well we’re able to reduce spending when we are forced to sell assets, standards of living may decline rapidly as well.

It’s a risky path to eventual bankruptcy

Why do we persist? We’re not 100% sure we’ll go bankrupt. And if we do, we’re not sure when.

We fool ourselves that because parts of the future are uncertain, we can safely ignore it altogether. (You might be thinking of the climate debate, too.)

Saying we can’t predict the future with certainty does not justify being willfully blind to the direction we’re heading. See Dean Wormer Was Right! for more on willful ignorance.

We can choose to start passing the marshmallow test at any time. You can do your part by stepping off the treadmill of excess consumption.

Be well.

Why not consume things that will make you smarter without costing you a penny? Stay sharp by subscribing to read my stories.

Member discussion