Jump Right In, The Water's Fine (Newsletter 067)

Greetings fellow travelers!

People can get used to almost anything. Our baseline happiness is surprisingly resilient, which is a testament to human adaptability. We are less affected by both good luck and bad luck than we think we will be. Whether a person wins the lottery or suffers a traumatic accident, most people's lives revert to the mean level of satisfaction they held before the event.

This very adaptability also means we often don't respond to changes in our lives, even when the cumulative effect is dramatic. Think of everything that's happened in the last fifty years: the Vietnam war, Nixon's impeachment and resignation, the oil embargo, stagflation, the space shuttle explosions, the end of the Cold War, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, wars in the middle East, the dot.com crash, the financial crisis, and the elections of Obama, Trump, and Biden as President. To say nothing of the global pandemic, lockdowns, unprecedented government spending, and now widespread inflation.

Our GDP mushroomed from $1.3 billion to almost $25 billion, while the U.S. population grew by more than 130 million new Americans, to 338 million today. We've had a half century of fantastic change, with wild highs and some equally fraught lows. And throughout it all, how do you think Americans rated their happiness?

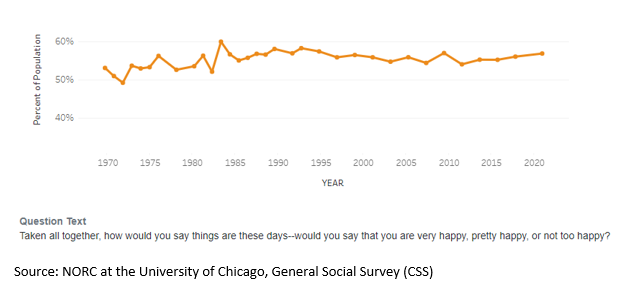

Lucky for us, the University of Chicago has been surveying national attitudes all this time. Here's the chart for the percentage of Americans responding, "Pretty happy" to the question "Taken all together, how would you say things are these days – would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?"

Some slight jogs up and down in the 70s and 80s, but the flat line over the last thirty years is remarkable. For all it seems we're complaining all the time, most people say they are pretty happy and have been saying so for a long time.

Americans' sticky level of perceived happiness raises an interesting question: Have our living circumstances actually been relatively unchanged all this time (i.e. we have it just about as good as did people a couple generations ago), or are we simply ignoring all the changes around us, for better or worse?

And by the way, how can we know which it is? After all, pointing out objectively how much better (or worse) things are is kind of irrelevant if people subjectively feel exactly the same. It could also be that some things are getting objectively better, while other things are getting objectively worse, but the net effects cancel each other out.

For example, a growing population expands the collective workforce, which brings new great ideas to market and grows our GDP. But more people also put a burden on our creaking infrastructure and adds to congestion and crowding.

I am trying to help answer the question by providing an objective look at America in the Paradise Found series. Being outside the U.S. for 25 years, the changes wrought over time seem more apparent to us now that we're back. We see things with relatively fresh eyes, at least compared with everyone who's been here this whole time.

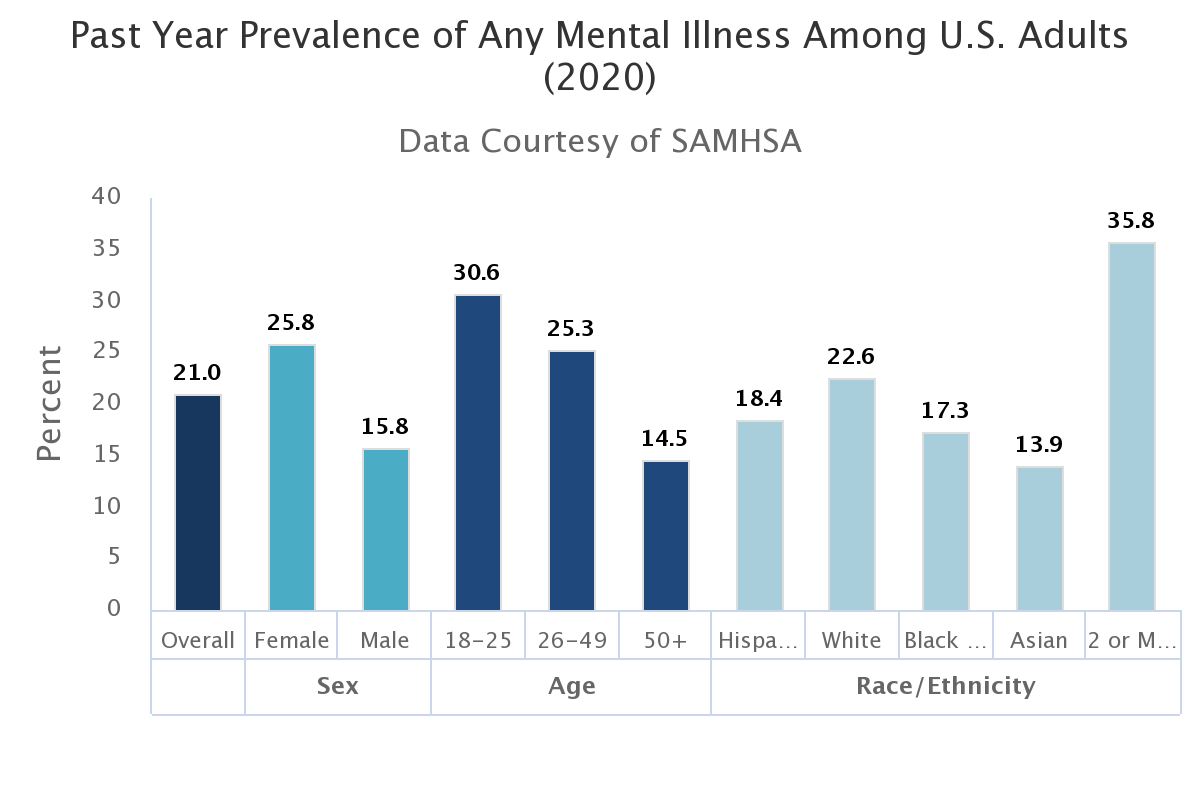

So far, my answer is that what you see depends on where you look. Our national wealth and accomplishments are unquestionably historic, but it appears that our very success is undermining the foundations for future progress. While the same number of people today say they are pretty happy as did fifty years ago, a lot of people today are apparently suffering from some kind of mental illness:

This chart from the National Institute of Mental Health draws on data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Lots here to explore, beyond the fact that young, white women are apparently suffering disproportionately. I wish the happiness surveys also broke down their results by further categories, so we could tease out additional insights.

For now, let's focus on the mental illness trend by age. Young adults have starkly higher mental illness rates than do those over fifty, twice as high. We can explain this in part by acknowledging that with age comes a certain acceptance, if not wisdom. Because you have seen more, you take the daily outrages less personally. It's not about you, the world is just unfair sometimes.

Perhaps we can give our younger colleagues some credit, however, for being less willing to accept the status quo. It is possible they are the ones seeing the world accurately, and they do not like what they see:

- A century of abusive environmental practices seems to be bearing bitter fruit.

- Decades of profligate spending have left Americans with untold billions in debt that the people who incurred won't be around to pay.

- Our roads and buildings are crumbling around us, and despite record spending, we can't seem to stem the decay.

- Education costs more than ever and is not demonstrably effective at preparing students for the workforce. American kids' reading and math performance is back to where it was in the 1990s.

- Healthcare costs more than ever and is not leading to better outcomes for many Americans. Our life expectancy has also declined to where it was in the 1990s.

- We've never had an older crop of politicians in all the leading positions of government, and none of our leaders seem willing or able to address our pressing problems.

My goodness, the wonder is that more people aren't depressed.

Interacting with our fellow citizens can sometimes lead us to shake our heads. I can't say for sure whether people today are more selfish than they were a few decades ago. But our recent experience observing up close a broad cross section of travelers provides strong evidence supporting the idea. In In Strangers' Living Rooms, we explore what might be behind selfish behavior in public.

Thanks for having me in your living room today, or wherever you're reading this. I hope the visit has not been intrusive, and I look forward to talking with you next week.

Be well.

PS – Check out my Career Path column this week, which is about Dealing with One-issue Stakeholders. What are some ways to respond to people who believe passionately about their issue? You may not care about it as much as they do but ignoring them may not be your best course either.

I'd love to hear from you. Just hit reply to tell me what's on your mind or leave a comment on Klugne directly. If you received this mail from a friend and would like to subscribe to my free weekly newsletter, click here.

Member discussion