Try Using Economics To Steer Your Life (Newsletter 058)

Greetings friends!

You might greatly improve your quality of life by applying basic economic principles to key choices you make: where to spend your time, what goals to pursue, and how to measure your success.

By understanding how supply and demand (or more simply, competition) applies to much of your life, you can compete more effectively. You do this by focusing on areas where you have a competitive advantage, which comes from more than your efforts and abilities. It also comes from where you apply your efforts and abilities.

To begin, let's consider a few basic economic principles. We see lots of evidence in the news and public debate that many people don't appreciate these simple rules:

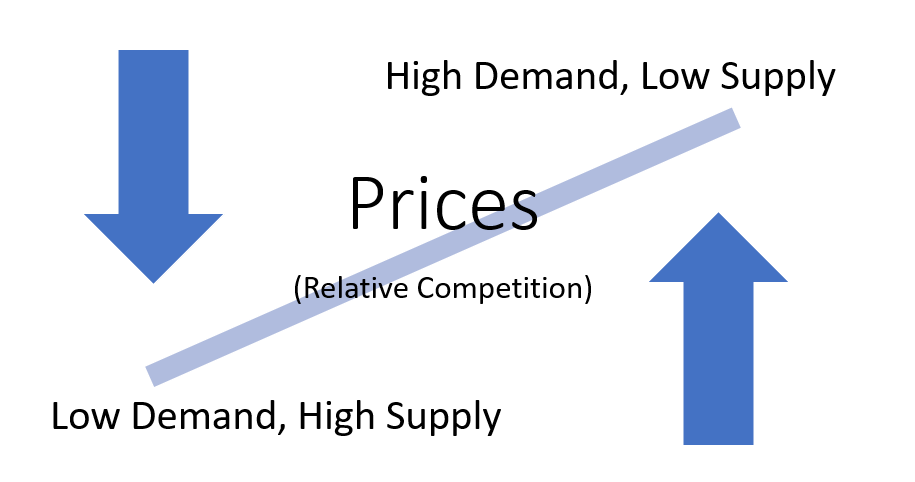

- When demand for goods and services remains constant but supplies are scarce, the prices for those goods and services increases.

- When supplies for goods and services remain steady but demand increases, the prices for those goods and services increases.

- And when demand is high and supplies are short, prices can increase dramatically.

All this is another way of saying that competition for limited resources is real and has an impact on what things cost. When we look at changes in supply and demand, we're effectively measuring how stiff the competition is for the underlying goods and services. The more people who are trying to buy a car, book a flight, or fill their tanks with gas, the more that competition for limited resources will result in prices going up.

The basic rules of competition apply in many areas of life beyond buying goods and services. When there is massive demand but only limited supply, competition will be fierce. This explains why it is hard to get into the top schools, join certain professions, or get jobs in fast-growing companies. This basic rule explains why some salaries are much higher than others, why it's so hard getting elected to political office, and why very few individuals become models, movie stars, or best-selling authors.

Most of us spend all our time focused on the same things as everyone else: money, power, fame, possessions. We have been dazzled by the supposed prizes on offer and are blinded to the opportunity costs and likelihood of achieving them. Economics offers another way of running the equation to achieve success: look to places where competition is much scarcer (i.e. demand is lower), but where the rewards are still great.

At its heart, Stoicism offers such a refuge: little competition for great rewards. These rewards are not the same as others chase. You will not hear a Stoic telling you to pursue a big bank account and a corner office, although these things may come. Instead, set your sights on attaining wisdom and you will be amazed at how wide open the field is. You do not need to compete for scarce resources, because few others are looking for the same goal.

Not only that, but competition on the path to wisdom does not make your task harder. The more people seeking wisdom, the more you can support and benefit each other. Wisdom is one of the few areas in life where greater demand creates greater supply. (A related area I know of is lawyers, where supply seems to create demand. That is, greater numbers of lawyers typically create more legal issues.)

Best of all, the reward for seeking wisdom is a well-ordered mind following reason. Specifically, with wisdom you will be satisfied and happy without regard to any of the scarce prizes your colleagues run after. Realizing you do not need money, or job titles, or possessions to be happy is incredibly liberating. The question to ask is do you want to be successful as it is traditionally understood, or do you want to be happy? The difference lies in whether you seek to attain wisdom.

The Moral Letters this week nicely illustrate today's lesson. In Moral Letter 115 On False Fronts, we talk about looking beneath the surface of things. When we take things at face value unquestioningly, we accept other people's ideas about what is valuable and important. But when we consider how often the conventional approach leads to dissatisfaction and dismay, we should be encouraged to think again.

The Stoic approach of looking past the surface to the substance of things only appears hard, well, on the surface. Peace of mind awaits the person who is comfortable thinking for themselves about what things are really worth. The cost lies in caring less about what others think.

In Moral Letter 116 On Slippery Slopes, we look to a related economic principle: do things we enjoy in limited doses remain good for us when we consume them in ever greater quantities? Or if you like, when supply becomes greater than demand, what happens to the value of the item?

For most physical things that give us pleasure, there is a risk that our indulgences turn into vices. Then, what once made our lives better starts to make it worse. In this letter we discuss knowing how to deal with limits, and what sorts of pleasures we can safely indulge in and how.

If we pursue what everyone pursues, we can expect the regular laws of supply and demand to apply to our efforts. Look around you to see how satisfied your colleagues are before you sign up to the same game.

Instead, here is a tip I am happy to share freely: when we pursue wisdom at our own deliberate pace, we might find that the things we need to be happy are already in our possession.

Be well.

I'd love to hear from you. Just hit reply to tell me what's on your mind. If you received this mail from a friend and would like to subscribe to my free weekly newsletter, click here.

Member discussion