066 - On Stoic Virtues - Moral Letters for Modern Times

The outward appearance of a person tells you nothing of their inner value. Consider Stephen Hawking who, though immobilized in his wheelchair, roved the limits of the universe and greatly expanded human understanding. Would you say his broken body was worth less than the perfect specimens gracing this year’s fashion week? And when their perfect figures have become disfigured from the passage of time, will you then consider them to be worth less than when they were parading down the catwalk?

Today I want to talk with you about the Stoic virtues, and how to value the pursuits that people seek. This is not only not a trivial question, Deuteros, it is the only question that matters. The lack of clear answers drives people to distraction, and to seek happiness in things that can never deliver it to them. So what then should be a person’s highest pursuit? How do they best live their lives? Let me describe what the Stoics believed.

The Stoics tried to distinguish between different types of pursuits, and counted the first order as those that we should actively seek out: joy, peace, victory, good children, the welfare of our country. Then there are second order conditions that we do not seek out, but which we call upon as needs arise: bearing up well in cases of suffering and severe illness. And finally, there are conditions about which we are indifferent, which are not in our control, including our physical stature.

The Stoics believed that virtue based upon reason, the well-ordered mind you have seen me write about so much, is the highest state a person can achieve. To control the mind and your response to circumstances is the greatest good, and this is what the wise person seeks to attain.

There is an important consequence of putting reason at the pinnacle and I would spend some time with it to make sure you follow. The virtuous result of a well-ordered mind applying reason is the same regardless of the circumstances. That is, whether you are enjoying a positive pursuit in a measured way for the right reasons, or enduring a hardship for the right reasons, you are applying the same reason with the same result. Thus, there is no difference between the Stoics’ first and second order pursuits, even though the circumstances of the person differ greatly.

“Do you mean to say,” you ask, “that there is no difference between pleasant and unpleasant things, and that we should value them equally?” As regards virtues, Deuteros, all that differs between them is the circumstances in which they are revealed. Because we regard reason as the ultimate virtue, then a hard circumstance cannot make the virtue less valuable; a joyous circumstance cannot make the virtue more valuable. The virtue itself comes from doing things consistently, directly, and with reason. You cannot be more right than being right in your conduct, and the circumstances only change your behavior, not the reason for your behavior.

I sense you are resisting so let me make the point another way. The virtuous act is one that you do willingly. If you are reluctant, hesitant, afraid, or otherwise resistant, you are not behaving entirely of your own will. You will be confused, you will have doubts. Thus, you are not behaving willingly, and your act is not the virtuous one of the well-ordered mind. When you are following reason, you will handle a beneficial tailwind or a serious hurdle in the same way, willingly.

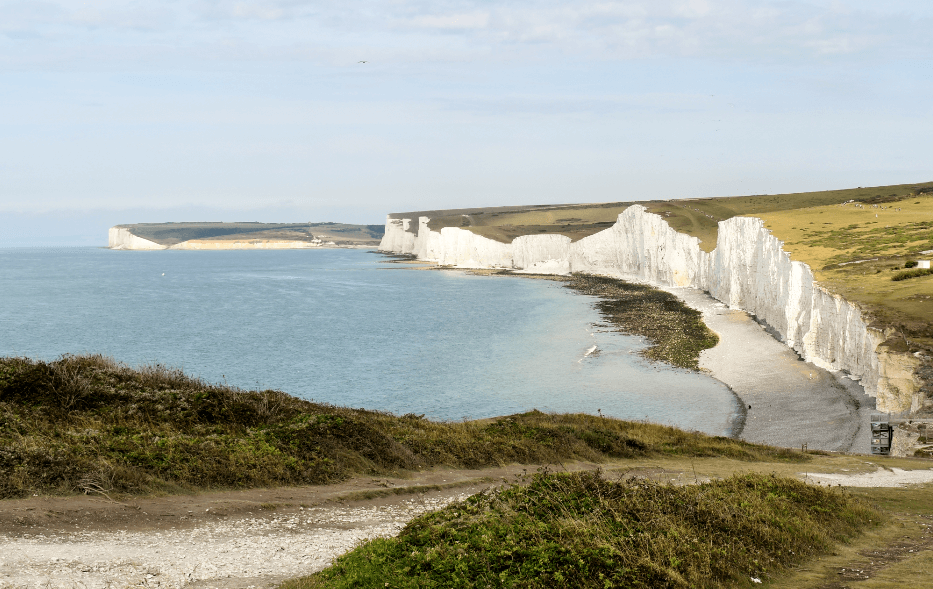

There is of course a difference between pleasant and difficult circumstances, between joy and pain, and we are good at recognizing the differences. Where we are able to choose, we will choose joy and avoid pain. The value in dealing virtuously with either, however, is the same. Virtue is the master of the emotions that otherwise threaten to submerge us, whether it be under waves of pleasure or waves of pain.

It is not just the external circumstance of the moment that virtue allows us to overcome. Reason also brushes off external consequence. That is, though all may criticize you, condemn you, or cast you out, the wise person does the virtuous deed all the same. The right course of action is the same regardless of the praise or blame of others that is forthcoming.

Reason also overcomes differences among individuals, as I noted above. Whether you are as rich as Jeff Bezos, or as poor as the migrants making their way across the border river with their few possessions held above the water in sacks, the virtue of your actions is not higher or lower because of your belongings. In the same way, it does not matter whether the person is tall or short, handsome or ugly, healthy or ill. All the things that vary according to good luck and bad luck cannot affect virtue: possessions, money, the person, their position. These all come and go, unevenly distributed and alternatively given and taken away.

Consider friendship, which is one of the things that Stoics saw as desirable. Would you value a friend more for being rich than poor, for being tall and handsome instead of short and ugly? Would you say they are your friend so long as they hold an important position, and turn your back on them once they’ve left office? This would not be true friendship, because friendship looks to what is within. Or consider one’s children. What parent says they love their children differently based on their height or hair color? That because this one has the gift of gab, while the other is shy and retiring, they should be ranked in another order?

To sum up, my dear Deuteros, virtue does not depend on circumstance, either of the person, or of the situation, including whether the act is pleasant or unpleasant. The virtue we seek, reason and the well-ordered mind, is the same in all circumstances. Feeling joy with self-control and suffering pain with self-control are the same. Yes, we desire the first and admire the second. To think that they are of different value, though, means you are placing value on external things and not intrinsic ones, on the clothes and not the person dressed in them.

The external things that the masses pursue provide fleeting and empty pleasure. The things that bring them anxiety are similarly just shadows, not worthy of fear. With reason you can master your emotions and the senses. Your senses do not know what is virtuous, they merely take in what is given. Only the mind is able to recall the past, to look forward to the future, to reflect on the meaning of the moment, and ultimately the purpose of life. It is reason that allows us to judge the good or evil of things.

The greatest good a person can possess is to conduct oneself according to what comes, in accordance with reason. Whether you are seeking out a positive pursuit or enduring a negative situation, you have equal opportunity to apply your reason. We prefer that our bodies are strong and healthy, and that we take delight in the things we have. We would rather not suffer ill health or serious setbacks, but the value in them comes from enduring them willingly, with a calm mind.

I say if you have to choose, Deuteros, remember that rising to a challenge can be a greater test than not letting yourself get carried away with good fortune. Thus we should desire to be strong in adversity even more than we should bear good fortune with equanimity.

Be well.

Member discussion