Why It's So Hard Being An American Overseas

Greetings friends!

There are many reasons why it's tough being a U.S. citizen living outside the United States. Today I'll focus on just one that seems minor but has significant consequences on expat quality of life.

Banks don't like us anymore. For years now, we've been as welcome as dog poop on dress shoes.

It’s nothing we did, at least not individually. It’s something we all were doing, or rather not doing, that led to this sad state of affairs.

Have you been caught up in the hassle of keeping an account or opening a new one? I’ll give you the backstory and end with practical tips on how to navigate the new waters.

Americans Have Long Been Required To Report Their Foreign Bank Accounts … and Didn’t

The Bank Secrecy Act gave the Department of the Treasury authority to collect information from U.S. persons who have financial accounts with financial institutions located outside the United States.

Specifically, U.S. persons are required to file a FinCEN Form 114 — Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR) if the aggregate maximum value of all foreign financial accounts exceeds $10,000 at any time during a calendar year.

That all worked fine for many years in the sense that (i) most Americans had no idea of the requirement and (ii) there was no practical consequence for failing to file their foreign bank account reporting form or FBAR.

- It’s estimated only 131,000 FBARs were filed in 2001 despite there being several million Americans living abroad then.

What Changed This Happy Balance?

In 2003, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (the FinCEN of Form 114) delegated FBAR enforcement authority to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

Over the next few years, the IRS got the idea that millions of Americans at home and abroad were hiding their money in foreign bank accounts to avoid paying U.S. taxes.

Never mind that the vast majority of Americans have foreign bank accounts because they live and work in foreign countries. And that these Americans comply with foreign tax laws on their earnings such that very few individuals have any further U.S. tax obligation in respect of them.

Thus began a Quixotic crusade by the IRS to ferret out foreign bank accounts, whatever the cost.

Their hunt for Americans with foreign accounts ultimately led to Congress passing laws in 2010 that created burdensome and expensive new reporting requirements for both banks and individuals all over the world.

These rules have bedeviled U.S. citizens ever since.

What Do the New Rules Say About Foreign Accounts?

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) was passed as part of the HIRE Act. It generally requires that foreign financial institutions and certain other non-financial foreign entities report on the foreign assets held by their U.S. account holders or be subject to withholding.

In plain English:

Foreign banks must report to the U.S. the assets of any U.S. persons with an account.

If the bank does not get the customer’s consent to report the account, the bank becomes liable for withholding 30% of any U.S. source income relating to those accounts.

The utterly predictable consequence:

Many foreign banks simply stopped dealing with U.S. citizens. The costs of compliance are massive, and the consequences of making a mistake are horrible.

The banks that decided to keep working with U.S. citizens pushed the cost of compliance onto their customers.

An American wishing to open or maintain an account must agree to allow the bank to disclose their account and its holdings to the IRS every year. The individual must also typically certify that they have reported their accounts to the IRS.

Simple Enough, You Say, and What’s the Big Deal?

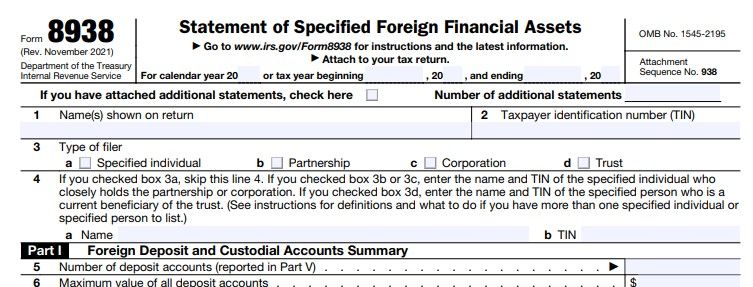

Well, the HIRE Act also requires U.S. persons to report, depending on the value, their foreign financial accounts, and foreign assets on a completely new form.

Americans must still file every year FinCEN Form 114 (the FBAR) with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. Now they must also file Form 8938 with the Internal Revenue Service as part of their tax return.

The problem:

Most Americans abroad still do not file an FBAR, and many do not file U.S. tax returns. With an estimated 9 million Americans abroad only 1.4 million FBARs were filed in 2021.

Many ex-pats have no U.S. tax liability because, again, they are paying taxes first in the country they live in. Either the foreign tax credit or the foreign income exclusion is enough to mean they owe no U.S. taxes.

But now to keep their bank accounts open, their bank effectively forces them to file their FBAR and a U.S. tax return on which they must declare their accounts. This is confusing for many Americans and expensive for everyone who needs help preparing their returns.

What’s a Law-Abiding Citizen To Do?

The IRS has shown itself to be persistent as an angry badger. I don’t see them giving up on pursuing American citizens and their bank accounts all over the world.

Here’s what I recommend you do:

- Because the penalties for failing to file your FBAR are severe (easily adding up to more than the maximum value of the account), if you have non-U.S. accounts, you should file an FBAR every year.

- Filing the FBAR is actually not too difficult, once you’ve practiced a few times. You can do it online for free on the FinCEN site.

- If you’re single with more than $200,000 in assets (double that if married and filing jointly) in your foreign accounts, you should file a U.S. tax return that includes Form 8938. Your bank is going to report your accounts.

- And if you earn any income or have a foreign account with $10,000 or more, your safest course is also to file a U.S. tax return.

I know this is burdensome, but you’ll sleep better knowing the IRS isn’t going to come looking for you.

Be well.

Hit reply to tell me what's on your mind or write a comment directly on Klugne. If you received this mail from a friend and would like to subscribe to my free weekly newsletter, click here.

I posted a version of this article on Medium originally in the publication Synergy.

Member discussion