Why Experts Are The Last People We Should Listen To

We need more experts like we need more coal-fired electricity plants. (Wait, do we need more electricity from fossil fuel?)

On just about any subject you choose, you will find conflicting opinions. So-called experts weigh in on all sides. But what does expert even mean? Does it mean someone who has spent one minute more than you thinking about an issue? Or must it be someone who has devoted their lifetime studying nothing else? The first we do not consider to have special knowledge beyond the average. The second is not sufficiently aware outside their field to provide advice in context. And because no issue can be handled in isolation, but must be considered in context, the deep subject matter expert is of little practical use either.

Take the question of lockdowns as a means to slow the spread of a pandemic. Where did the expertise to justify them come from originally? Would you believe from a study of the Spanish flu, teasing out correlations from limited data of actions taken more than a century ago? But after a transfixed world watched the Wuhan lockdown and its apparent result, there was a stampede to follow their example.

This illustrates two problems with so-called expert opinions. First, it takes sometimes scant evidence to establish an opinion that becomes canon. Consider the once widespread advice that you should drink eight glasses of water a day. It seems this came from a reference in the 1945 Dietary Guidelines published by the Food and Nutrition Board of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences to consuming one milliliter of water for each kilocalorie consumed. Thus, average male consumption of 2,500 calories a day meant 2.5 liters of water a day. This was later reinforced by nutritionist Frederick Stare who advised drinking at least six glasses of water a day. No science backed up either opinion. See What drove us to drink 2 litres of water a day?

And, second, the number of people who agree with something is often meaningless as a signifier of whether the idea is a sound one. It takes but a single valid criticism to outweigh a thousand “consensus” views. Keeping with our theme of drinking, it took Barry Marshall swallowing a solution containing pyloric campylobacter and developing gastritis to crack the staunch resistance of the medical community to the idea that bacteria could be a cause of ulcers. He and his colleague Robin Warren later received the Nobel Prize for their discovery of the role of Helicobacter pylori.

If we can’t trust the dabbler in ideas, and the deep experts have blind spots, how about we consider the well-rounded professional as the best kind of expert? That is, someone who has spent time studying an issue, but has not made it their exclusive life’s work. Surely we must believe that hard work and study can bring wisdom, or universities have a lot to answer for. (Actually, universities do have a lot to answer for, but that’s another topic. See Americans Are Not Competitive Enough.)

The problem with well-rounded professionals, and it’s not theirs alone, is twofold: (1) they are just people, which means error-prone, and (2) they are skewed by incentives. On the first point, we make mistakes. We are willfully blind, seeking out information that confirms our existing views and ignoring contrary evidence. Well-meaning does not mean impartial. On the second, incentives are always at play in human affairs, though they may not be apparent to the casual eye. A person may be affected by personal interests like ego, reputation, and funding, but also societal interests like the direction of public policy.

None can be considered impartial who has an interest in the outcome. You might be thinking what’s the point, because this means practically no one can be impartial. I’d agree with you, and that’s the point: because we are all affected by our interests, it helps to know what those interests are before we blindly accept an expert’s opinions.

As an example of how these interests, errors, and biases play out in practice, consider that on a topic as fundamental to humankind as what we should eat to stay healthy, a century of expert advice has created more confusion than clarity.

The advice on what to eat is conflicting and frequently changing, because so many people have an interest in the outcome. Food companies fund studies to influence dietary guidelines and sell their products, scientists want to get their research published and so tweak statistics into significance, and newspapers write exaggerated headlines about studies to attract attention. See Nutrition Advice Gives Me Indigestion.

So what to do? Ignore all experts? No, that would be going too far. Let us listen to them, for purposes of determining what is factual in their assessment. Experts have no monopoly on facts. You are entitled to the same facts, and should distrust an expert who will not share the facts underlying their opinions. If fact, you may dismiss entirely such experts.

And give no special weight to an expert opinion drawn from facts. If the expert is a human, they are flawed. If the expert is being used for a partisan purpose, knowing their bias you must discount their opinion. Evaluate their relative “expertness” on an issue, from dabbler to demonically possessed, and judge accordingly their ability to craft solutions in context. At best, you can consider their opinion as you would any other reasonably informed person. You can decide yourself what makes a person “reasonably informed.”

The way to avoid being unreasonably influenced by an expert is to make them the last person you listen to.

Gather some facts, and think about the issue yourself. If the question at hand turns on a fact, question the sources of facts. If the question is amenable to opinion, by which I mean reasonable people can disagree about the solution, form your own opinion. If at all, only then should you consider the expert.

Before you put this into practice, please consider one more thing. You’re probably a person too, which means you suffer from the same fallibilities, biases, and incentive traps as do experts. This means you really shouldn’t trust yourself either when it comes to forming opinions.

The only responsible stance is not to hold strong opinions unless you are willing to put in some work. Specifically, you must first make sure you can convincingly argue the other side’s point as well as they can. Otherwise, while you can certainly have opinions, don’t be too sure of yourself. Keep an open mind, and seek out information that would contradict your weakly held hypotheses. Take no comfort in consensus opinions.

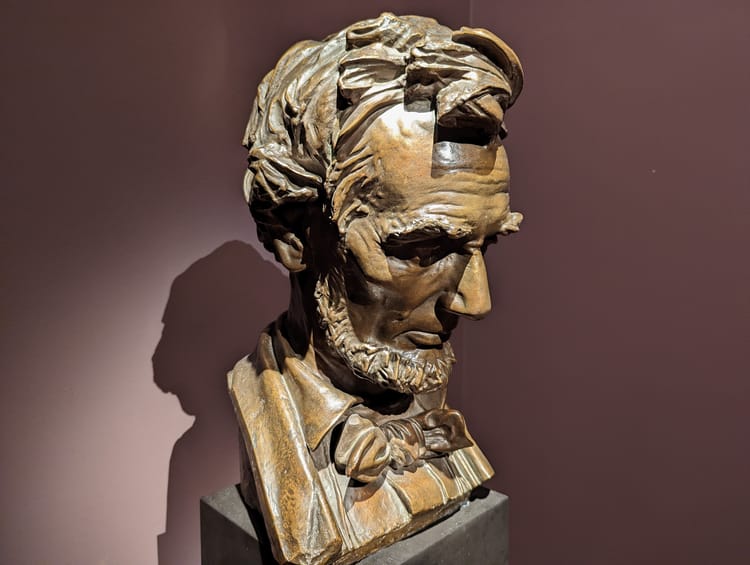

This remains a useful rule of thumb: believe none of what you hear and half of what you see.

Be well.

Member discussion