The West Owes this Couple a Huge Thank You

Greetings friends.

For the first time in 60 years, China’s population did not see annual growth. This bombshell was contained in a January 17, 2023 press release issued by the National Bureau of Statistics of China.

I’ll explain what that means for the West and why we have one particular couple to thank, at least in part. This requires a brief detour into population demographics.

I’ll finish up with ideas on how to improve the quality of our long-term policy decisions more generally.

How Have Longevity and Population Growth Developed in the 20th Century?

The world has extended the average human lifespan by decades in the last century. We’ve gone from a life expectancy of around 50 years to closer to 8o years today.

This was accompanied by a dramatic increase in the total population, from less than two billion in 1900 to over eight billion today.

So it’s understandable that in 1968 when Paul Ehrlich and Anne Howland Ehrlich wrote The Population Bomb, all trends were pointing towards massive overpopulation. They predicted worldwide famine would soon result, which triggered something of a panic.

Why Is It So Hard to Make Long-Term Predictions?

There were several problems with the Ehrlichs’s doomsday predictions.

It’s worth reflecting on some key lessons for anyone who makes long-term predictions based on current trends.

- Complex systems involving human behavior are highly dynamic. People respond to incentives, which inevitably alters the trend line.

— As an example, let’s say people move to a popular city in numbers that suggest fantastic growth ahead.

— Then housing prices jump, traffic gets jammed, unemployment goes up, and crime rates rise. The rate of growth predictably slows or even reverses. - Complex systems contain both predictable and unpredictable elements.

— We can say it's likely technological breakthroughs that have the potential to alter the trend line will occur, but breakthroughs are unpredictable both in scope and timing. When they occur, they alter trendlines in ways that were formerly unimaginable.

— Unforeseeable negative events also may occur. While we know that natural disasters and global pandemics will occur, we cannot say when or what the circumstances will be. - Complex systems are affected by many inputs, which makes predictions more than a few years out unreliable.

— Over a short period, we can more reliably estimate inputs that have a material influence on our models.

— The longer the forecast period, the greater the likelihood that the estimates of critical inputs will vary, making the model’s predictions less useful.

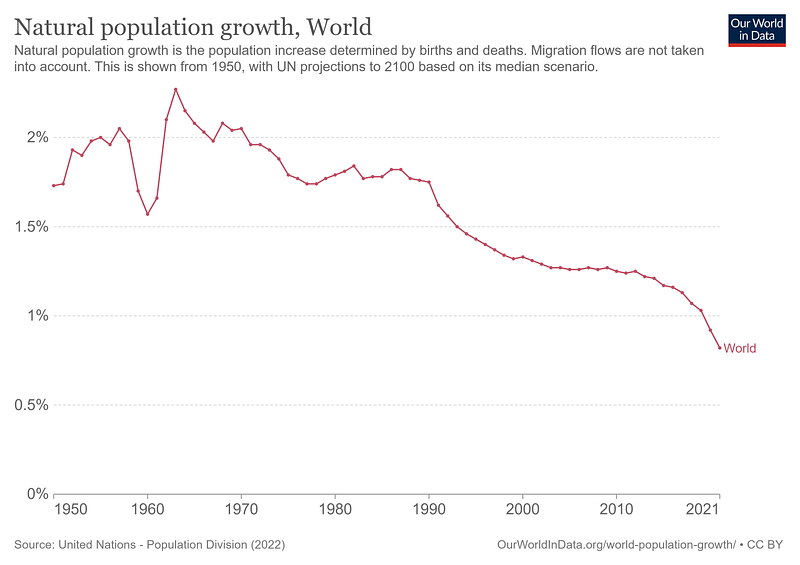

In the case of global population growth, 1968’s 2.08% growth rate coincidentally represented a peak from which the world has been declining ever since.

China’s Overreaction Was Understandable

The whole world was alarmed by the predictions of impending global famine.

The ideas suggested in the book The Population Bomb included raising taxes on childbearing and childcare goods, offering incentives for sterilization, supporting the prenatal determination of the child’s sex, ensuring easy access to abortion (for example of undesired girls), and establishing a Department of Population to “take whatever steps are necessary” to maintain the desired population size.

Luckily for the West, these ideas were never implemented.

China took the concern entirely more seriously, however. They had in recent memory the Great Famine of 1959–1961, in which tens of millions of people starved.

That the Great China Famine was largely self-caused did not dissuade policymakers from thinking they should act once more to prevent future famines due to overpopulation.

China began implementing various family planning policies in 1970, including raising the age of marriage and calling for fewer and more broadly spaced births. Between 1980 and 2015, China restricted families to a single child, the so-called one-child policy.

This all had the desired effect of slowing the growth of China’s population. All good, right? Perhaps not.

What Are Some Consequences of an Aging Population Together With Slow Growth?

Simply put, more people living longer in retirement supported by fewer people working is a dangerous combination.

It puts financial stress on countries because the revenue from working citizens is insufficient to provide comfortable retirements for the elderly.

Wealthy countries can devote more of their resources to solving this problem, both by committing to spend more on retirees, but also by increasing wages to the point that they attract people to enter the workforce, including via immigration.

In contrast, developing countries that experience this demographic squeeze before they have sufficient resources to manage it can expect economic pain and civic unrest. That’s exactly the unfortunate situation facing China today.

Where as recently as a few years ago economists predicted the inevitable growth of China’s economy to become the world’s largest, now the chances are good that China will never reach this milestone.

Be Careful What You Wish For

There are lessons here for the astute observer. I mentioned several above regarding the dangers of making long-term predictions.

Another set of lessons relates to thinking carefully about the unintended consequences of our actions. Policies intended to achieve one outcome may or may not succeed, but they will create unintended consequences along the way.

With some careful consideration, these unintended consequences are foreseeable. Thus, in any debate about new policies, be they social, environmental, or economic, we should discuss not only the desired outcome but also any unwanted though predictable consequences of the new policy.

We should also frequently revisit policies after we start to implement them. We should assume that our first attempt will be imperfect, and be prepared to adjust and adapt quickly. In this way, we remain alert to changing conditions and can change course as needed.

The two things we should never do are assume that our long-term predictions will be correct or consider that the first solutions proposed are sufficient.

Be well.

Hit reply to tell me what's on your mind or write a comment directly on Klugne. If you received this mail from a friend and would like to subscribe to my free weekly newsletter, click here.

Member discussion