All the Right Data, All the Wrong Conclusions

Greetings friends!

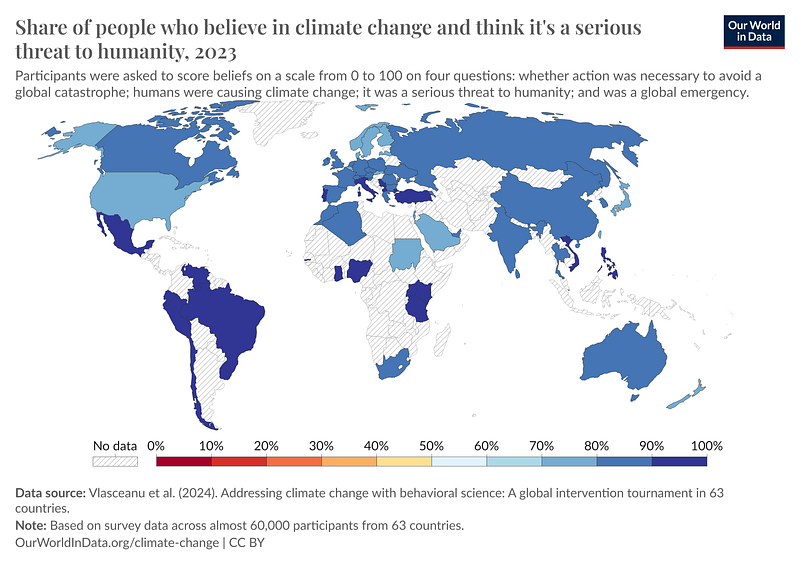

The normally sober Our World in Data organization published an article recently entitled “More people care about climate change than you think.” It presents a case study of how well-meaning people can draw entirely wrong conclusions.

As far as collecting data and presenting it in colorful charts goes, Our World in Data is unsurpassed. But as to interpreting what the data means, they are just as prone to bias and wishful thinking as the rest of us.

It’s also possible Our World in Data has knowingly cast objectivity to the curb to promote what it knows to be a false agenda, but I prefer the charitable interpretation that they’re merely wrong.

The climate change hypothesis — simply stated

Using data from large, global surveys, Our World in Data describes how individuals, when asked, profess by large majorities the following attitudes:

- “Belief” in climate change, including that it is a serious threat to humanity and a global emergency (some 86% of us, apparently).

- A majority of those surveyed (72%) support climate policies, including carbon taxes, expanding public transport, and taxes on airlines.

- Fully 69% of respondents said they would be willing to contribute at least 1% of their income to tackle climate change.

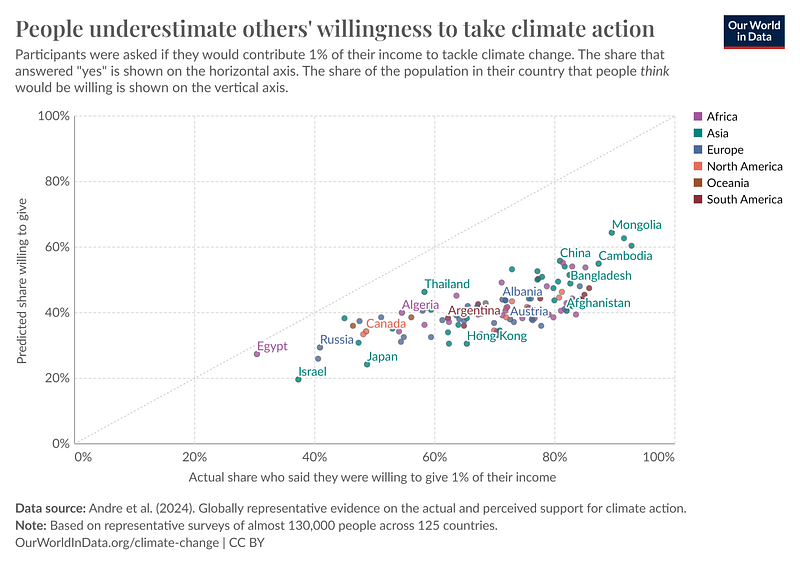

The flaw in our thinking… apparently

Although 69% of us would happily hand over our income to solve climate change, when asked in the same survey how many of our fellow citizens we think would do so, our estimation of their goodwill plummets: We think just 43% would do the same.

This finding is consistent across every country surveyed, and the results are stark. Everyone believes others would not be as willing to pay up. This holds for the general public and the so-called “elites.”

Our World in Data calls this a “perception gap.” They explain how individuals often think of themselves more highly than they do others — which they refer to as individual optimism and societal pessimism.

Our World in Data also suggests (without irony, as far as I can tell) that the reasons people believe not everyone is on board with climate activism include:

- Social media amplifies extreme opinions, such that people who are opposed to climate action drown out the average voter who supports it.

- Mainstream media may be suppressing the story that most people want climate action because disagreements get more clicks.

- Presenting “both sides” of a debate can give the mistaken impression that there are two sides to a debate.

The glaring flaw Our World in Data missed

We live in an era where many climate activists are quick to mock dissenting views and seek to de-platform and censor people who merely ask questions. Individuals are thus discouraged from speaking out against the supposedly consensus view.

Even in the eminently reasonable communities I frequent, posing reasonable questions about climate topics engenders outraged and even threatening responses. I’ve linked a few articles below* that amply demonstrate the point.

At the same time, responding to a survey offers a cost-free virtue-signaling opportunity. I show myself to be a model citizen if I confirm what I think is the orthodox view. I risk ostracism or worse if I express my doubts. It’s an easy choice.

In these circumstances, we must place little weight on what people say in surveys. Luckily, we have a much more reliable indicator of what people genuinely believe than what they say. What’s that, you ask? It’s what they do when given a choice.

Our actions handily reveal what we truly believe. The economic theory of revealed preferences says that people’s genuine beliefs are shown in what they do.

The idea that we’d be willing to spend even a fraction of our income on climate change has been conveniently tested in recent years.

- The French tried in 2018 and again a few years later to increase taxes on gas and diesel fuel by just a few cents per liter. The virulent protests by the “Yellow Vests” almost brought down the government.

- Even the consummate environmentalists, the Swiss, rejected multiple government proposals to raise taxes on gas. Apparently, Switzerland’s 0.1% contribution to the world’s CO2 is not a global catastrophe Swiss citizens want to pay to eliminate.

Doubling down on the alarmist message is counterproductive

No intelligent and honest person can say that humanity faces a global emergency from the couple degrees increase in global temperatures climate scientists forecast over the next century.

I know some people have been led to believe we are facing an immediate, existential crisis. Activists do glue themselves to roads and throw soup on paintings out of genuine, if profoundly misguided, fear that humanity’s very survival is at risk.

When we brand people as deniers for raising good-faith questions about the costs and benefits of proposed climate measures, we should not be surprised when survey respondents profess agreement with the mainstream view.

But nor can we act surprised that when people are called to spend their own money, their actions reveal considerably less enthusiasm.

The current activist playbook favors even stronger messaging to ensure no dissenting views are ever heard. This risks driving potentially helpful feedback underground while failing to change many minds.

As an alternative, how about we consider why it is that so many people are asking questions? Why not have a serious discussion about what it would cost to prevent temperatures from rising a couple of degrees (and what will happen if we do not), and what other societal priorities we’ll have to forego as a result?

Until we have such discussions, we can expect to see the “perception gap” only widening.

It’s not that people don’t realize what’s going on. It’s rather that they understand exactly what is.

Be well.

To see the world clearly, we must first recognize when people are misleading us. Read more of my work to be misled less often.

* Here are some articles raising questions in good faith about climate topics. See how climate activists liked them!

Member discussion