If You Don't Know The Costs Of Your Solution, You're Part Of The Problem (Newsletter 040)

Greetings friends.

Identifying problems is easy. You are not the first person or the only person to detect things that aren't working perfectly. I tell new hires that identifying problems is the easiest thing for an employee to do.

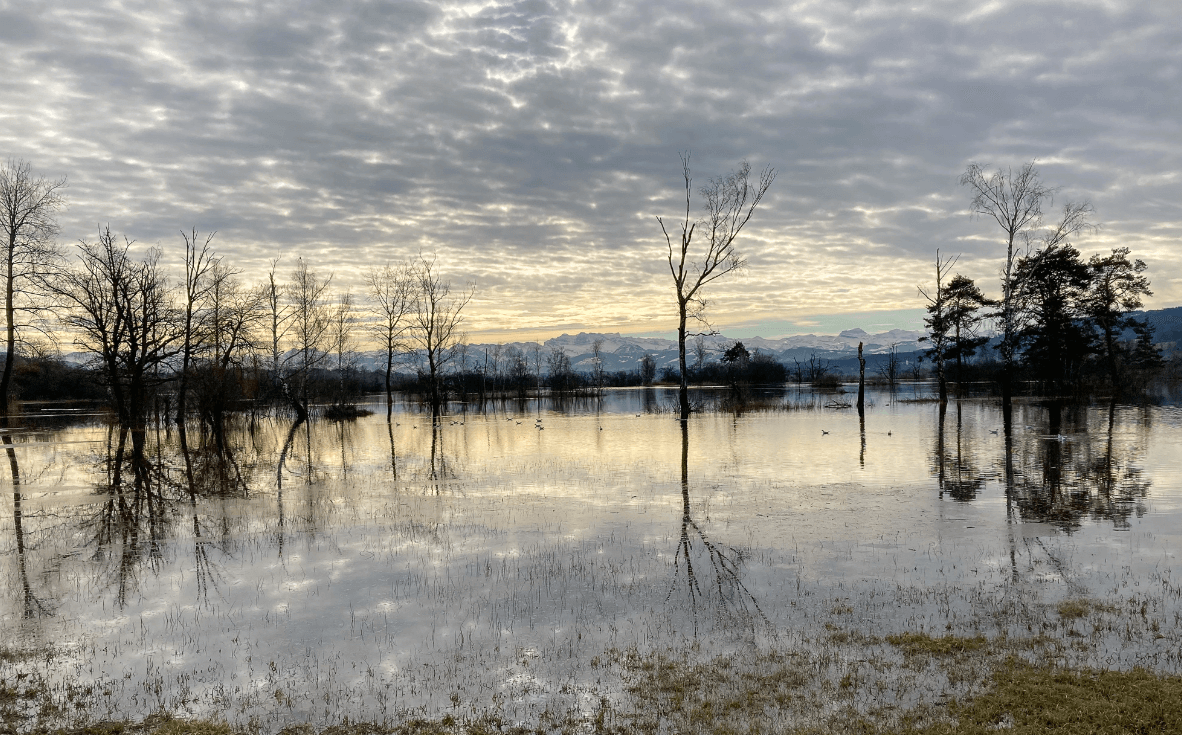

This week we identified a problem with our move to the United States. It was one that we had not anticipated, at least not to the correct extent, although in hindsight it should have been obvious. You can read about it in Flying Again. We are starting to organize our impressions of the U.S. and will start posting articles in the Paradise Found series more regularly.

We think we have a solution to our immediate problem. In the work setting, I tell employees that proposing solutions is easy. You are not the first person or the only person to come up with any number of solutions to the problems you've identified. In proposing a solution, however, you are already ahead of the many people who stop with carping about problems. We should appreciate and celebrate the creativity that comes from putting oneself in a problem-solving mindset.

Here's where things get difficult fast: identifying which problems are worth focusing on, and which solutions are worth pursuing among many possible approaches. Doing so requires a blend of strategic thinking and real-world pragmatism that most people only gain through experience. Let me explain.

We typically have a rich buffet of problems laid out before us at all times. Faced with this abundance, many people choose to address problems they feel are manageable. That is, smaller problems with relatively quick solutions. Is someone requesting your input via email? That's easy. Take a few minutes and respond to them. This type of problem-solving can be quite satisfying. You are checking items off your list and making visible progress.

The expedient path to problem solving is a risky path. Notice first how the number of small problems never diminishes. Each task we accomplish provides a fleeting burst of pleasure but is rewarded by two more tasks. Next notice how often we spend our entire day in a succession of what we thought would be brief moments of quick answers. The many little things we chase after mindlessly eat up the day.

If you are purposeful, you may have carefully thought about your important priorities. These are the strategic things that you believe will have the greatest impact. Ask yourself how much overlap there is between the small daily problems you usually spend time on and your strategic priorities. If you are like most people I know, the answer is not much.

You can find reinforcement in this week's Moral Letter 080 On Training To Improve. We explore the risks in focusing on superficial things, even if they are individually beneficial, if such activity means we neglect our all-important training of our well-ordered minds. In other words, not getting distracted by the satisfaction of solving small problems.

The further you advance in your career, the more you will find people looking for you to help solve their urgent problems. This is only natural, but you must be aware of this key fact: other people's problems are not necessarily your problems. And helping solve other people's problems is often not the best use of your time. Now ask yourself this: Do you have a clear sense of what is the best use of your time?

Take a moment and write down what you think are among your greatest potential contributions to your company. How do you (or can you) add value? Especially for lawyers, keep in mind that your greatest contribution may be avoiding negative outcomes. People overweight additive initiatives, like acquisitions, introducing new products, or entering new territories. But often tremendous value hides in helping ensure your company and colleagues do not, pardon the phrase, f— things up.

To summarize where we are so far: problems large and small always clamor for our attention. The things we spend time on by default are unlikely to be the most important problems. It is helpful to for us to carefully consider the ways in which we add value because this helps us identify potential problems worth focusing on. Let's assume we have done all this and are looking at a short list of strategic problems.

Now we come to the heart of today's topic: how to devise solutions worth pursuing to strategic problems. Such problems typically have no easy solutions. They wouldn't be strategic problems otherwise. I've seen talented, successful managers devise solutions that would unquestionably address a strategic problem, but still fail to make progress. Why is this?

Otherwise promising solutions fail for many reasons, most prominently these: (1) underestimating historical and cultural factors supporting the status quo: and (2) focusing too much on the benefits without considering the costs. Let's explore both points.

As mentioned, it's easy to spot suboptimal situations at work, in organizations, and in society. Before diving into problem-solving mode, it is critical to ask how the situation developed and why. Although some problems develop spontaneously, there are very often explanations behind the things that appear screwed up to us today. It helps to understand how we got here before trying to set a path to a new destination.

Moral Letter 079 On Studying Beneath The Surface explains that we need careful thought and reflection to understand why things are the way they are. And why when sifting through possible solutions, looking to those that have worked well in the past is often more reliable than reaching for a novel solution.

Change requires effort, and significant change requires extraordinary effort. Because people are creatures of habit, we tend to keep doing what we have been doing, even if we know it's expensive, inefficient, or downright harmful. Ask anyone who has tried to change their eating, exercise, or spending habits. The burden of change today is magnified when the reward is distant in time. The more we have to change for a speculative future reward, the harder the challenge.

Thus, the first reason potential solutions fail is that we fail to account sufficiently for human stubbornness, which tends to preserve the status quo. The obvious correctness of a solution doesn't help overcome this. In a work setting, successful implementation means you must be willing to either (a) invest extraordinary effort in pushing your solution, or (b) identify and piggyback on existing initiatives and cultural currents underlying the behavior you want to change.

Even if you are able to invest extraordinary effort, you are well-served to spend time understanding your company's culture. Who among your colleagues has a respected voice and will support you? Are there other successful initiatives already underway to which you can add your own initiative?

Think of your company as a slow-moving river of molasses. Don't try to push your boat against the flow, or uphill. You may be able to gradually shift the course, but remember you are dealing with incredible momentum.

Now to the second reason solutions fail, which is not sufficiently considering the costs. These costs include the active resistance from those who are disadvantaged by upsetting the status quo and the unintended consequences our solution gives rise to. It is because of these factors that even successful projects regularly take twice as long and cost twice as much as planned.

You can forecast likely costs more accurately by conducting pre-mortems. That is, assume your project has failed (or stalled, or taken longer, or cost more, etc.). Now describe all the reasons why. This will help you plan for those obstacles, and perhaps avoid some of them. But mostly it will help you come up with a more realistic assessment of what substantive change behind your initiative will require.

You should be sobered, if not depressed, upon concluding your pre-mortem exercise. Significant change requires extraordinary effort, which comes at the cost of all the other things you cannot pursue. If you are grand in your expectations, be humble at least in your estimate of how quickly you will proceed.

I'll end with an example to illustrate the dynamic. Most people agree human-caused climate change is a serious, global concern. The solutions seem obvious to policymakers: immediately and drastically cut carbon emissions, while shifting to renewable energy. A short reflection reveals, however, why the obvious solutions are destined for likely failure.

- We have not given enough weight to the historical context. Particularly that today's first-world economies developed on the back of low-cost energy delivered by fossil fuels. Today's developing economies are naturally interested in their own development, which cannot be accomplished cost-effectively with renewables.

- Consumers in many countries have grown accustomed to their current quality of life, which has been fueled by decades of steady or declining energy prices. To achieve net zero carbon emissions requires immediate cost and real sacrifice for the foreseeable future in return for a very long-term, speculative payoff. Should we assume that a majority of people will suddenly decide to put future generations' interests above their own? I suppose coordinated altruistic behavior by large groups of people is possible, but it goes against all historical precedent.

Climate change may well be the most important project for the world to work on. I predict we won't make great progress until we are considerably more transparent about the costs. Only then will individuals and societies be willing to consider whether the costs are worth the benefit. Importantly, seeing the true extent of the costs will trigger a search for alternative solutions.

When we push solutions without a clear understanding of costs, we do worse than impede progress. We lose time and waste resources pursuing solutions that are bound to fail, making an eventual effective solution that much harder to implement. That's why I say if you don't know the costs of your solution, you are part of the problem.

Don't be part of the problem.

Be well.

Member discussion