Is Your Country A GDPaholic? (Newsletter 022)

Greetings friends.

It sounds faintly obscene as a standalone suffix, but an "-aholic" simply denotes someone who is addicted to something. Another way to think of the term is "liking something very much and unable to stop doing or using it." You certainly have heard of the alcoholic and workaholic, and perhaps you know a shopaholic.

My coining of the phrase GDPaholic refers to countries that appear addicted to measuring their progress via growth in GDP. GDP is short for Gross Domestic Product, which means the total value of goods and services produced by an economy over a specific period, typically each year.

Today I will explore the appropriateness of various countries' use of GDP as a measure of their progress. My thoughts coming into this post modified over the course of researching it. I wonder what you will think once you've arrived at the end?

I am usually skeptical of arguments that place our time in history as a particularly special one. There is ample evidence that we're just as prone to over-estimating our brilliance in assuming that we've reached peak human performance. Great societies failed often in the past, and today's great societies are also likely to fail, sometimes spectacularly. But there is one area where we can unequivocally say the current era is unlike any other: growth in GDP per capita.

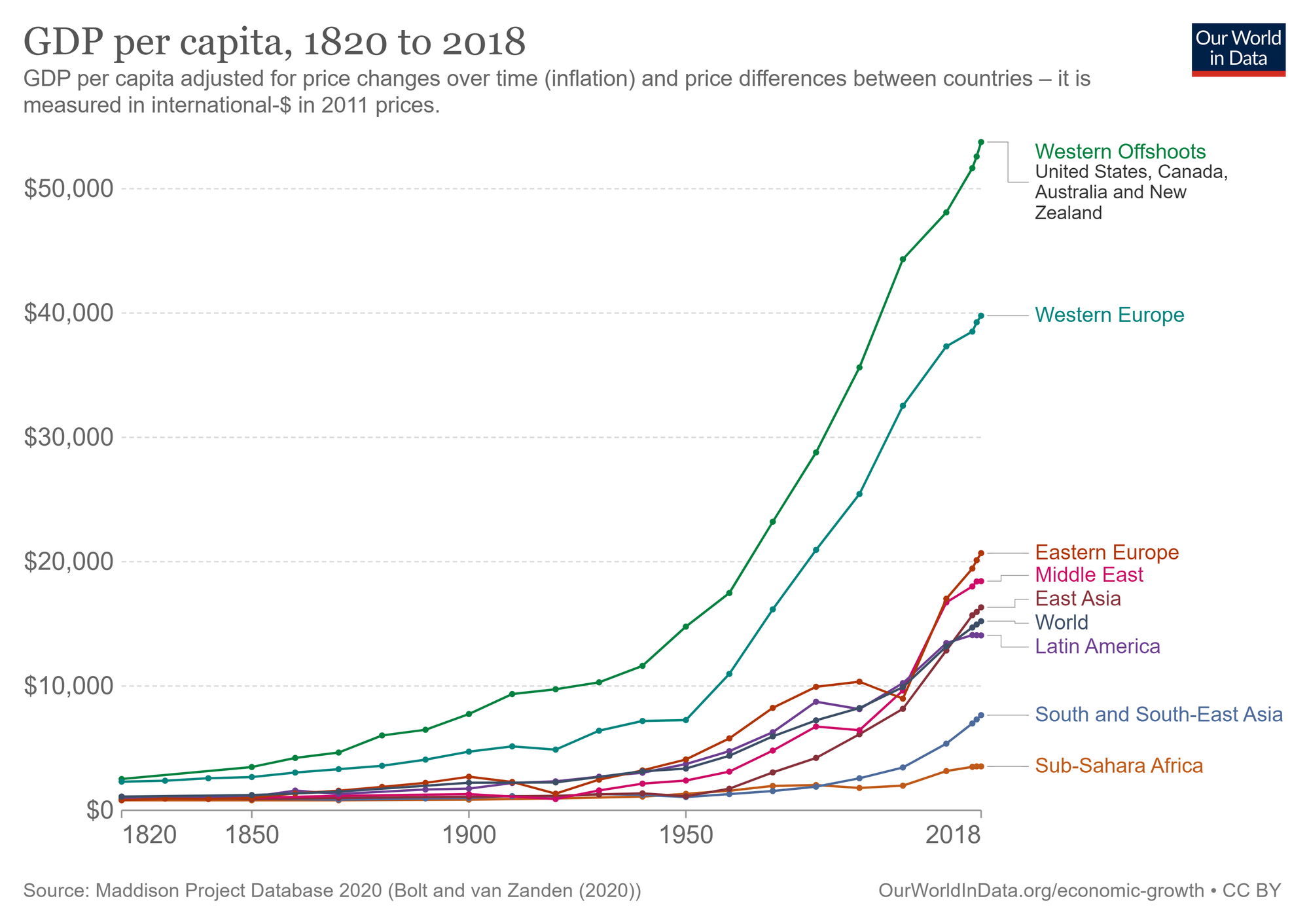

Here are a couple charts from the Our World in Data series on economic growth. This first one shows growth in GDP per capita across the world in the last two hundred years. You will note a long flat curve to the left and a steep rise starting in 1900s and accelerating in the 1950s. The long flat curve extends far out to the left for most of human history.

The growth in the world's economies has brought untold benefits for humankind. As the article in Our World in Data puts it:

Economic growth has allowed us to break out of the conditions of the past when everyone was stuck in poor health, hard and monotonous work, and malnutrition.

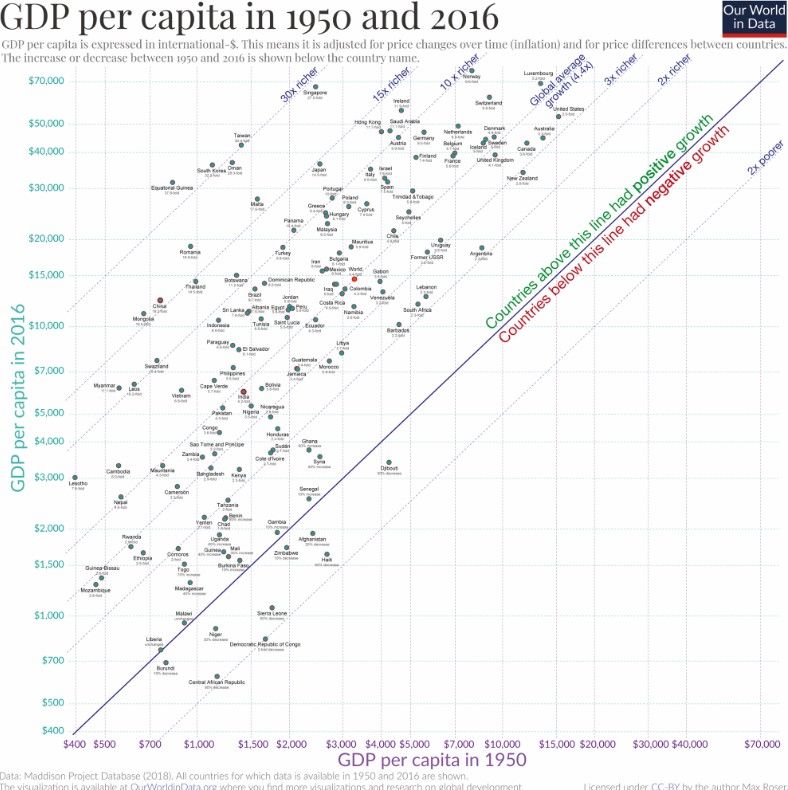

Growth in the last 70 years following World War II has been truly impressive and unprecedented in human history. This next chart looks complicated, but it's worth studying. It shows how many countries have become wealthier since 1950. Not only wealthier, but how many have become 10, 15, or even 30 times more wealthy.

The wealthiest countries in 1950 on a per capita GDP basis are shown furthest to the right on the chart. The United States was the wealthiest country in the world then with average GDP per capita of about $15,000. Because of massive growth in countries all across the globe since then, average global GDP today is now also almost $15,000. Or, as Our World in Data puts it:

Today the average person on the planet is as rich as the average person in the richest country in 1950.

"All well and good," I hear you say. "What about the citizens of all these countries? Are they necessarily better off because their countries have grown their economies?" Fair question. Our World in Data has some interesting data on this point as well in their Happiness and Life Satisfaction report.

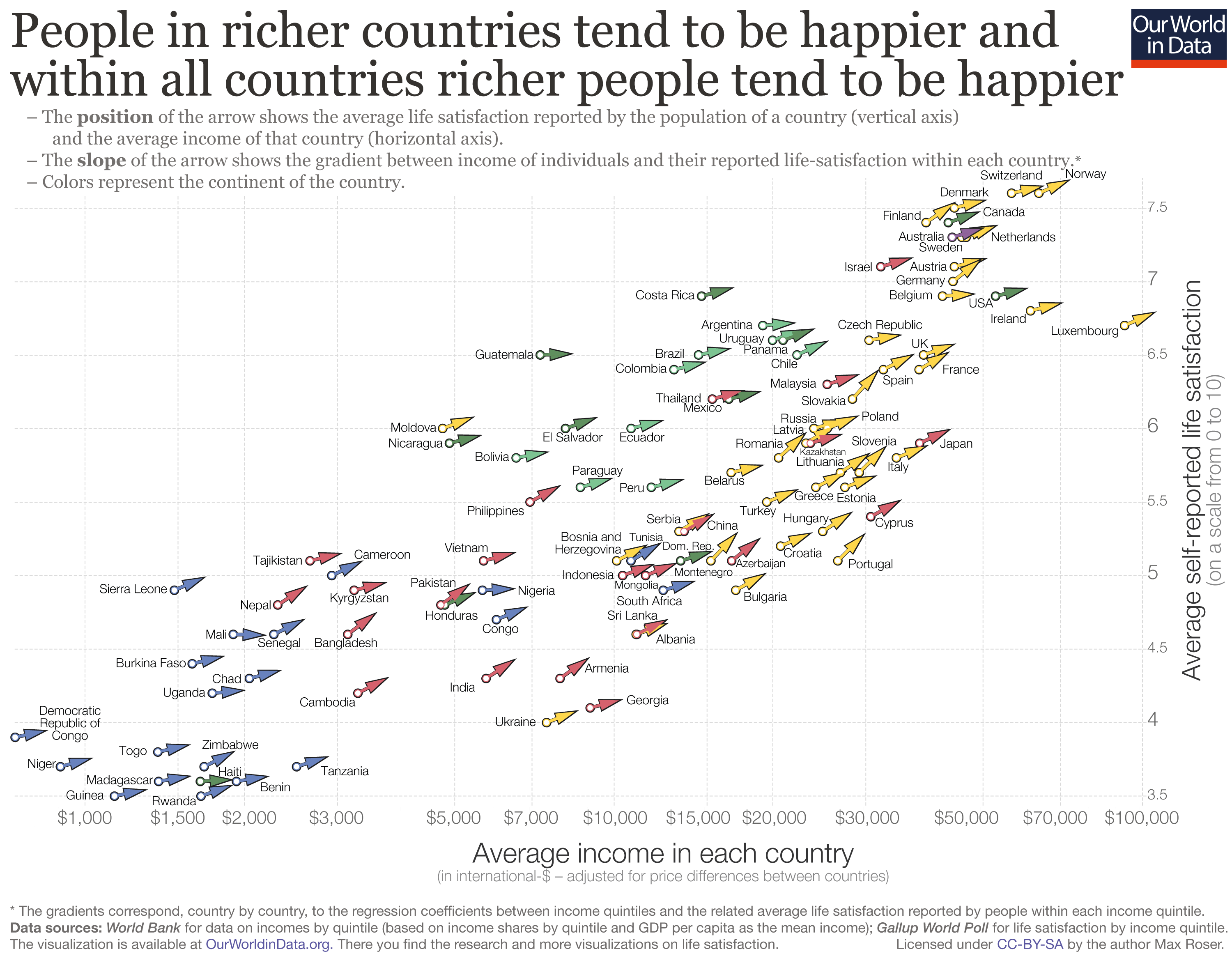

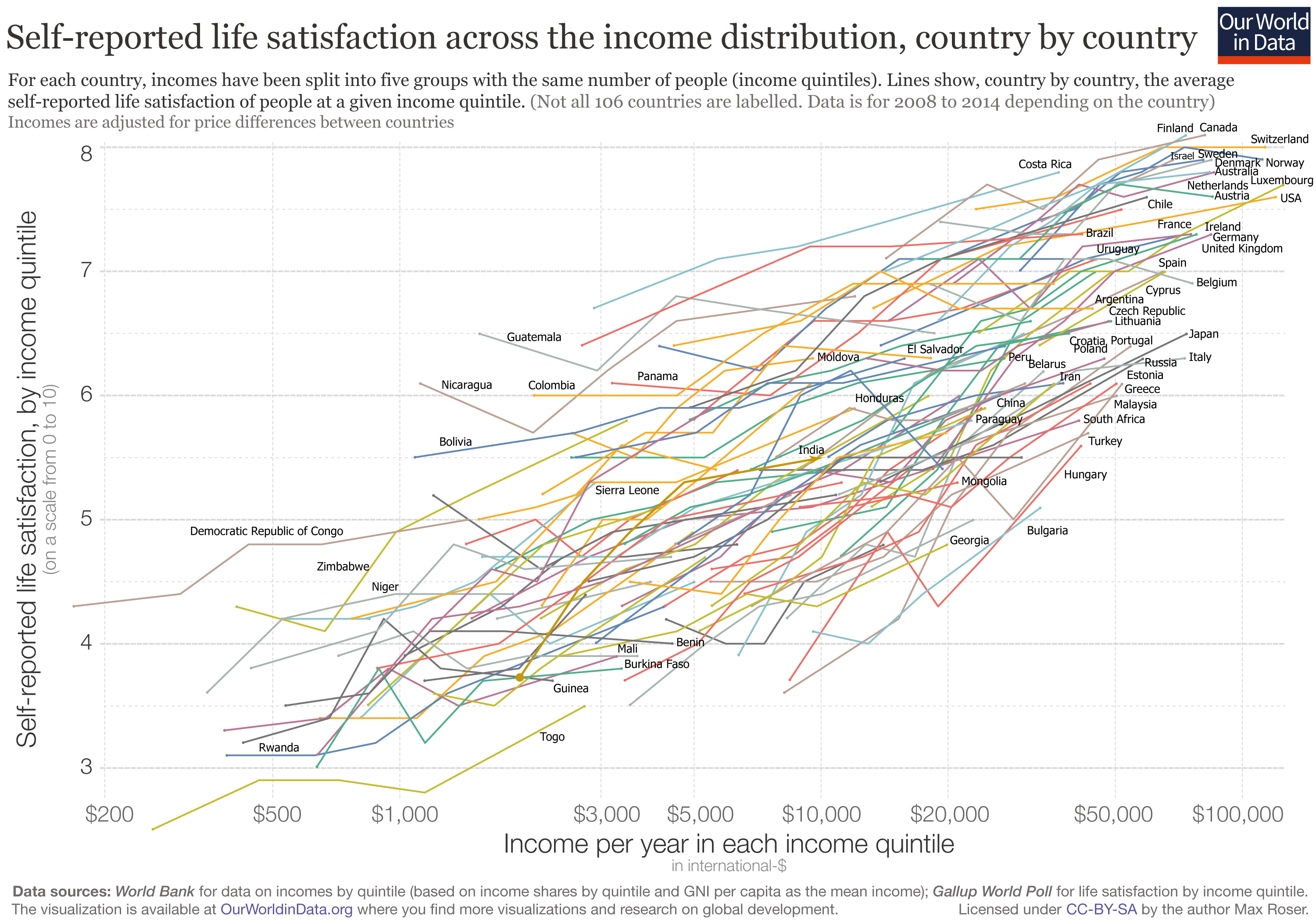

Here are two fascinating charts that show the correlation between wealth and happiness, and between wealth and satisfaction.

End of discussion, right? There is such a clear correlation between rising incomes and self-reported happiness and satisfaction. This seems to present a compelling argument in favor of using GDP growth as a metric of a country's progress.

Not quite, or at least perhaps not quite for all of us in already wealthy countries. Back in 1974, an economics professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Richard Easterlin, published an article describing a phenomenon that has since become known as the Easterlin paradox. As the charts above show so well, at any point in time happiness increases as income increases looking both across countries and within countries. However, looking at longer periods of time, happiness for individuals in a country does not trend upward as incomes continue to grow. How could this be?

A furious debate ensued. Well at least in academic terms. The paradox has not been resolved to this day, and in fact the underlying problem has been verified in many data sets across decades. Professor Easterlin and colleagues revisited the data, and expanded the countries to be studied. Each time, they found evidence confirming the paradox. From the 2010 update:

The striking thing about the happiness–income paradox is that over the long-term —usually a period of 10 y or more—happiness does not increase as a country's income rises.

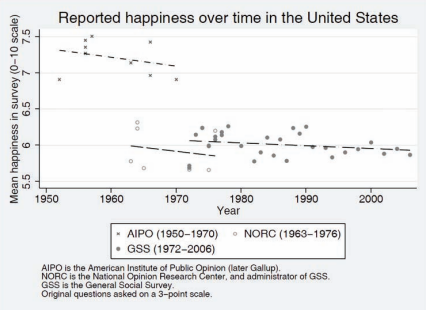

The 2012 World Happiness Report provides just as compelling a chart showing the flat line in reported happiness in the U.S. across multiple surveys and decades:

in some important countries, especially the United States, average happiness has not risen despite strong economic growth. This was so during the golden period of economic growth in the 1950s and 1960s, and also more recently, when even the top quintile of income recipients experienced no growth in happiness, despite huge increases in their income.

Professor Easterlin does not know what could be the reasons for the paradox, but he ventured a few good guesses that will be immediately familiar to the Stoic philosopher. From his 1974 paper:

economic growth does not raise a society to some ultimate state of plenty. Rather, the growth process itself engenders ever-growing wants that lead it ever onward.

And from the 2010 update, which also reviewed the experience of a number of emerging market countries:

clearly, the escalation of material aspirations with economic growth, reflecting the impact of social comparison and hedonic adaptation, are of central importance. No evidence has been forthcoming to suggest that poorer countries are somehow exempt from escalating material aspirations as income rises.

The regular reader of the Moral Letters for Modern Times will already have spotted the problem. The pursuit of material things does not necessarily bring happiness. And the attainment of material things creates a desire for more. If you want a refresher on the key Stoic principles and warnings in this regard, I recommend the following letters:

- Letter 017 On Wealth

- Letter 023 On Finding Joy In The Right Places

- Letter 027 On Things of Lasting Value, and

- Letter 031 On The Value Of Work.

Or if you prefer just a quick reminder, this quote from Letter 017 will serve:

To be content with little is difficult; to be content with much, impossible.

Professor Easterlin responded to critics yet again in 2017 with another update, Paradox Lost? I have to admire his persistence in taking the unpopular side of a research topic that seems to make economists and central bankers extremely uncomfortable:

New data for both the United States and countries worldwide, however, confirm that long-term trends in growth rates of happiness and real GDP per capita are not significantly positively related. The evidence indicates that it is Paradox Regained.

He's clearly growing tired of having to defend the basic proposition by conducting research over and over. As an aside, his troubles relate to people simply not wanting to hear the message, because it is inconsistent with what they want to believe. This happens a lot, and I will come back to the topic in a future letter. Professor Easterlin would like to reframe the debate:

It is time now to move on. The great value of measures of subjective well-being is that they reflect dimensions of well-being such as health, work, and family and social relations that are missed in traditional economic measures.

In other words, people all over the world are telling us something about their well-being that is not being captured in measures of GDP. They are telling us this loudly and clearly if you look for the data, and policymakers are largely ignoring them.

In terms of adopting a new measure of national progress to replace GDP, as far as I can tell only Bhutan has done so, adopting a measure of Gross National Happiness in 2008. I could use a dose of happiness now, if I'm honest. It is depressing to consider that we have raised the material wealth of humankind to unprecedented levels without also putting serious effort into checking that people's sense of wellbeing was rising along with it.

"Perhaps the measures of well-being and happiness are too subjective to be useful," you may be thinking. Actually, there are pretty good metrics to measure happiness and satisfaction, even though they are self-reported. I suspect the hesitation to adopt measures of national happiness lie far more in the fact that our leaders don't know how to drive citizens' happiness.

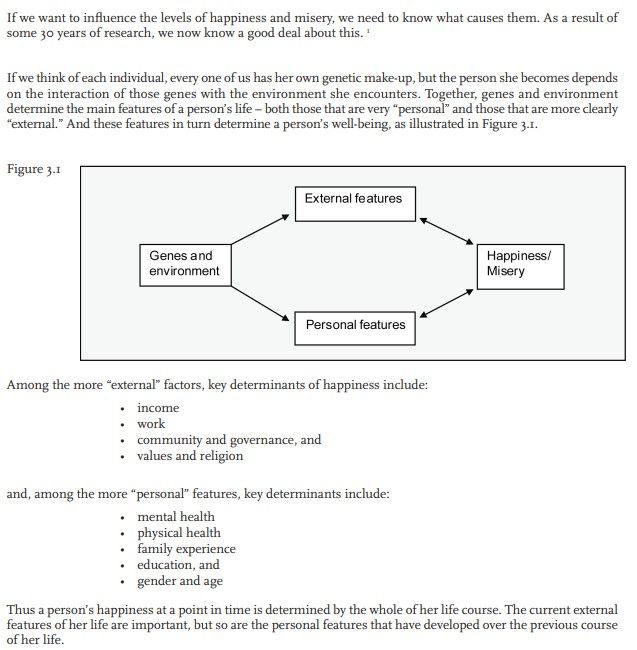

But researchers do have some ideas. Here is a summary from Chapter 3 of the 2012 World Happiness Report:

Oh, is that all? All of a sudden, I can sympathize with politicians' reluctance to make happiness the measure of a nation's success. The use of GDP as a proxy for success is not the first time that politicians have grasped at an imperfect tool that is easy to measure, but may not drive optimal individual outcomes. This week we also explore Central Banks' use of 2% inflation targets as a measure of healthy economies in Where Does The 2% Inflation Target Come From Anyway?

If politicians and bankers are not always measuring the right things, can philosophy help us? To the extent that Stoic philosophy is aimed at uncovering what it means to live a good life, it may hold some answers for us.

In this week's Moral Letter 043 On Rumor And Fact, I discuss one of the fundamental features of human nature that I think drives the happiness paradox:

people are poor at determining the value of something that stands alone, but we are savants when it comes to comparing two things.

Assuming your basic needs are met, which thanks to the fantastic growth in the world's economies in the last 70 years is true for most of us, your happiness depends on where you direct your gaze. Be careful whom you compare yourself to. Remember the lesson of the Olympic medalists (Would You Rather Win The Silver Or Bronze Medal?), and behave accordingly.

An optimistic thought to end on today, which comes from Moral Letter 044 On Class And Philosophy. The lessons of philosophy are available to us all, regardless of how we start out in life:

philosophy holds out to us the exact same opportunity, regardless of birth, gender, class, or wealth. Truly the way is open to all, though few tread these paths and fewer march confidently in a consistent direction.

The lessons do not come to us freely. It takes a sincere investment of time and effort to shape your mind to a new course. If the rewards are happiness and satisfaction that, while not captured in any measure of GDP, are nonetheless your most prized possessions, I trust you will agree your study is a sound investment.

Congratulations on having made it all this way with me today. It was an interesting journey, no?

Be well.

Member discussion