Aspirin Recommendations Make My Head Hurt

Imagine my surprise to see recently the widely reported news that taking a daily aspirin to reduce the risk of heart attack is no longer recommended by health professionals. My surprise was twofold. First, that medical professionals' widely held consensus understanding of basic preventative medicine could be turned entirely on its head. The American Heart Association itself noted that:

For decades, a daily dose of aspirin was considered an easy way to prevent a heart attack, stroke or other cardiovascular event.

What changed? The trigger for the current news cycle seems to have been a draft report issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. They describe themselves as "an independent, volunteer panel of national experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine." A variety of studies called into question the benefits of daily aspirin. In many cases, the risks of gastrointestinal bleeding outweighed the potential benefit of reduced heart attack risk. That is, taking daily aspirin was leading to worse health outcomes, not better ones.

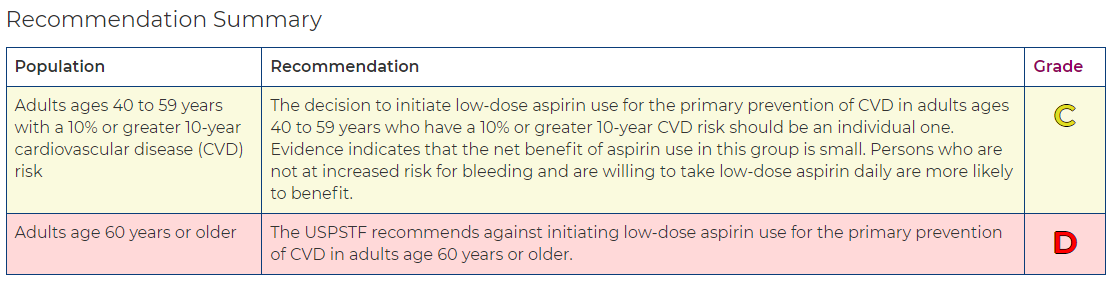

As a result, the Task Force now recommends against initiating low-dose aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults age 60 years or older:

Even if you have a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, the net benefit of aspirin use is small. The decision whether to use aspirin and in what circumstances is something to be decided individually with your doctor.

How could so many experts have been so wrong about something that everyone believed for decades? One reason is that once a belief becomes accepted as consensus view, experts no longer have reason to question their assumptions. Indeed, as we've seen in other areas, merely asking questions about experts' consensus view will get you quickly labeled as a quack or a denier.

To the credit of the medical profession, they eventually did carry out further studies to check whether their assumptions were correct. You might wonder why it took decades to discover they were wrong about something so fundamental.

I was thinking about this on my run today, and I realized that the number of people who make up the consensus view is not always a reliable indicator of whether that view is correct. "Why is that," you ask? Consider that the original hypothesis arises from, and research is usually conducted by, a small number of people and then shared with other experts in the field. Some of those experts may try to reproduce an experiment or extend it, but the large majority simply take the result on faith. That is, they believe it because of where it came from. Professor X is an expert, and if she says it then I believe it. In other words, they believe the results because other people believe they are true.

As soon as you have a small core of experts who believe a hypothesis, some of whom themselves believe it because a handful of experts are the ones who proposed it, what chance does the non-expert public have? Often, what we think of as the "consensus view" is really based on a small number of original studies that are taken on blind faith by the large majority of proponents. How much of what you and I believe is really based on Things Others Believe Are True, or TOBAT? You can remember this abbreviation by thinking that someone is always going to bat for their ideas.

I wonder who else was going to bat for the idea that aspirin was useful to prevent heart attacks? Is it possible that incentives played a role in there being no successful challenge to the recommendations for decades?

"I'm with you so far," you say. "But I thought you said you your surprise was two-fold? What is the other reason that you were surprised?" I'm glad you were paying attention, because it turns out I was not paying attention. For upon digging a little, I discovered the evidence that aspirin is more harmful than helpful is not new. In fact, this is (or should have been) old news.

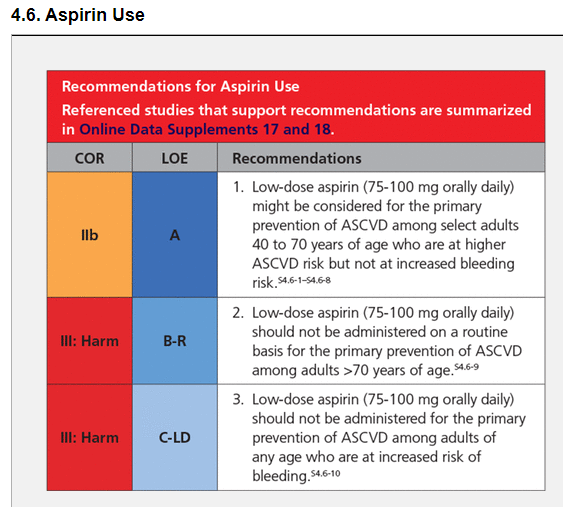

Already in 2018, studies were showing that the internal bleeding risk outweighed the potential benefit for many individuals. So much so, that in March 2019, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association updated their Clinical Practice Guidelines to recommend against the use of low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, except for certain high risk persons.

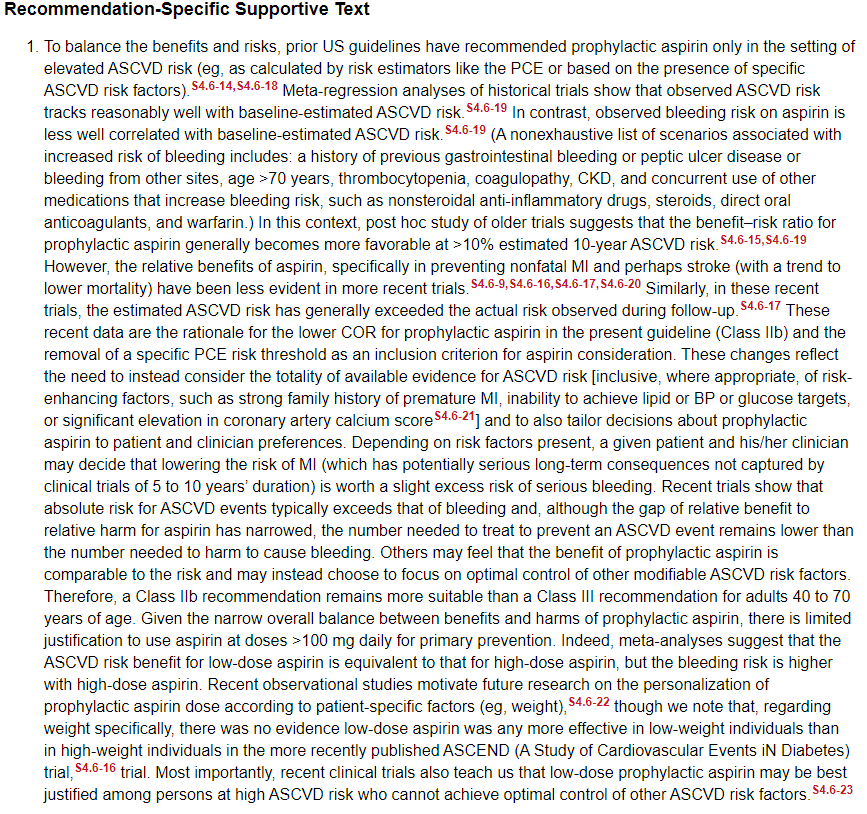

Now to be fair, their guidelines and accompanying explanation don't exactly trip off the layperson's tongue. Here's a short excerpt of how they describe the reason for the change in their recommendation:

I read this paragraph for an embarrassingly long time before I decided I needed an aspirin for my incipient headache. I could easily understand that reporters might have missed the significance of the findings and the change in treatment recommendations if this was their source. But it wasn't the only source.

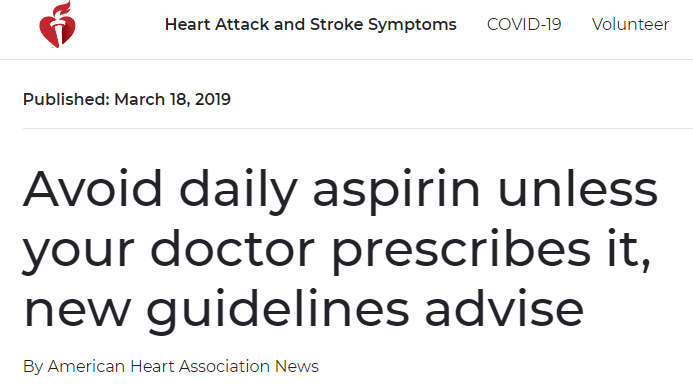

On the very same day that the guidance above was published, the American Heart Association released this news article:

Besides the glaring headline, this article describes the changes in plain English with no fancy words that might confuse a reporter or average reader. So what happened? Why didn't I hear anything about it until this latest story broke two and a half years later?

I guess some of you are sitting there saying, "You dummy. This is old news. I knew about it. My doctor knew about it. You're the only one who didn't get the word." That's entirely possible, but based on reactions from others, I don't think I'm the only layperson or doctor who never heard the news.

Not only that, but as recently as a few months ago, I was coming across prominent headlines like this one describing results presented at a conference of the American College of Cardiology:

I see now on more careful reading that they are talking about the use of aspirin following a heart attack or stroke, and not for preventative care. But the headline is certainly not nuanced is it?

Even today, a Google search on the topic reveals confusion and ambiguity:

If you are a reader of average intelligence, you might still be confused about whether aspirin is good for your heart, and when and whether you should take it. Are you really sure that if you march off to your doctor tomorrow with your questions that the answer will be clear to them?

It is disturbing that the power of the consensus view could stifle questions and dissenting views for so long. And that even when some scientists manage to start correcting the picture, that it takes even more time for the updated word to spread. Honestly, I'm a little sick to my stomach at seeing how science progresses so messily. But I won't go to the doctor. Why, you ask? I'm afraid she'll say "Take two aspirin and call me in the morning."

Be well.

Member discussion