Achieve Better Outcomes by Being Humble

Greetings friends.

I assume no one wants to fail at what they set out to do. I also understand that few people like to be reminded of their failures. But if by studying our failures we can improve our odds of future success, I say the study is well worth the discomfort. Even better, when we get into the habit of considering what could go wrong before we act, we can improve our odds of future success without having to first personally experience failure. Today's post explores how being humble can lead us to make better decisions.

My legal background taught me why being cautious is beneficial. Johnny Mercer wrote the lyrics in 1940 to what could be the unofficial in-house counsel anthem: Fools Rush In (Where Angels Fear to Tread). But I prefer the earlier formulation by Alexander Pope in An Essay on Criticism: "Foolish people are often reckless, attempting feats that the wise avoid."

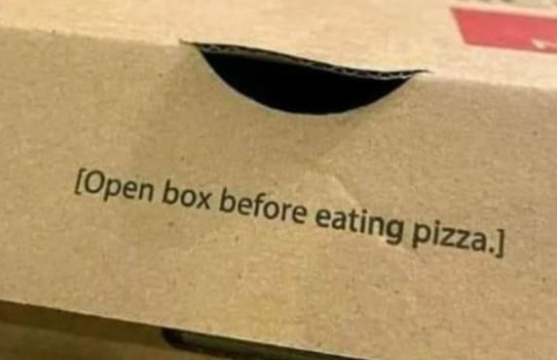

This could also serve as the rallying cry for every technical writer preparing warning labels for consumer goods products.

My own propensity for analysis suited well the Swiss-headquartered company I worked at for many years. The motto "measure twice, cut once" described our incremental, careful Swiss approach to many ventures. That said, while avoiding reckless behavior is a worthy goal, inaction is no answer. To make progress in business, in relationships, in life, we must act.

I recall our CEO frequently exhorting us to have a "bias for action." Analyze as necessary, but make sure not to be paralyzed by wanting to perfect our analysis. Sooner than we feel ready, plan to take concrete action. Even if the original plan is not perfect, we can also make corrections while we're implementing.

The ideal mix of analysis and action comes about when we plan to increase our odds of success while simultaneously contemplating how our plans could be frustrated. That is, asking what are the things that could go wrong and derail us. Planning for success while also contemplating failure is not intuitive, and most people can't do it reliably. In my experience, we like to focus on the pleasant daydreams of success rather than the ways we might flop.

Daydreaming of success is necessary and healthy, to a point. Taken too far, we risk falling into cognitive dissonance. We fall in love with our plan and see all the ways that it will be great. But then we tend to filter new information to fit our view of the world. We easily disregard contrary indications and ignore warning signs.

We have two potential countermeasures. First, when working alone, we can ensure our personal project plans include a "pre-mortem" step. It's usually helpful to do this sometime after starting your planning, but before you get too near the end. Say half-way through your planning as a good rule of thumb.

The purpose of the pre-mortem is to daydream again, but this time you imagine all the ways your project could be frustrated. Nothing goes according to plan. Why is that? Be broad in spinning out your disaster scenarios and try to come up with a lengthy list. Only once you've prepared a good list, rank your future obstacles in terms of likelihood, magnitude, and addressability.

Focus some of your planning attention on more likely risks of consequence that you can pragmatically do something about. Ignore small risks, unlikely risks, and risks that you cannot reasonably plan around. That said, try to be creative in considering potential mitigation before you dismiss a risk as too hard to plan around. Even if you can't think of a solution, if the risk is real and not unlikely, you might get some advice from others before moving on.

Our second countermeasure is available when we are working in teams. Then one person can be assigned specifically to think of the various spoiler scenarios while the rest of the team does its work. When the spoiler has a good list, bring the team together for a brainstorming session. This serves to review and expand the list, and then discuss possible countermeasures.

The benefit of the pre-mortem review goes beyond identifying weaknesses and improving your plan. A good pre-mortem includes asking "How will we know if things are starting to go badly? What types of information will we collect, and who will review it?" This helps shield you from ignoring negative data after you've started to implement your plan.

We humans value the things we invest time and effort into. The harder you and your team work on a project, the more difficult it is for you to objectively identify and assess warning signs. Knowing this, you can get help from people who are close to, but not directly involved in, your project. Have them monitor the data and assess for you whether you are on track or need to correct course.

Being well-intentioned, extremely smart, or fabulously rich – or indeed, all three – is no insulation against the cognitive dissonance that torpedoes good ideas. In fact, if you are all of these things, you are most at risk of ignoring warning signs. After all, you know in your heart your intentions are good, and your past actions have been highly successful. That's why you're the CEO and fabulously rich: you're smart and good at what you do.

I recently came across two very public demonstrations of this risk playing out in practice, which may serve as lessons for us mere mortals.

George Soros has made major investments in trying to bring about social justice reform. Let's assume his intentions are sincere. Here's how he recently described his approach:

I have been involved in efforts to reform the criminal-justice system for the more than 30 years I have been a philanthropist. ...

In recent years, reform-minded prosecutors and other law-enforcement officials around the country have been coalescing around an agenda that promises to be more effective and just. This agenda includes prioritizing the resources of the criminal-justice system to protect people against violent crime. It urges that we treat drug addiction as a disease, not a crime. And it seeks to end the criminalization of poverty and mental illness.

This agenda, aiming at both safety and justice, is based on both common sense and evidence. It’s popular. It’s effective. ... Some politicians and pundits have tried to blame recent spikes in crime on the policies of reform-minded prosecutors. The research I’ve seen says otherwise.

For those of you not following the topic, Mr. Soros has funded the campaigns of "reform-minded prosecutors" in cities across the U.S. This has led to the elimination of bail for many offenses and prosecutors declining to charge even serial offenders. Mr. Soros says the approach is based on "both common sense and evidence." As in, if we arrest and prosecute fewer criminals, we will have less crime. From one perspective this is entirely logical. But in the real world it is also absurd, because people respond to incentives. If we do not prosecute people for theft a certain number will steal with abandon, as store owners in many cities can attest.

What to make of the "evidence" Mr. Soros refers to: "The research I've seen says otherwise"? Has an argument ever been settled by a person referring to a study they found somewhere? The Internet is awash with conflicting and sketchy information. To a person experiencing cognitive dissonance, a single study confirming their deeply held belief easily holds off mountains of contrary evidence.

I previously wrote about our other smart, well-intentioned, billionaire, Mark Zuckerberg. See The Scariest Monsters Are Well-Intentioned. He claimed in a recent interview, without apparent irony or awareness, that the use of Facebook decreases polarization and teenage girls' mental health improves when they use Instagram.

He said that the research he'd seen supported his views. He also noted, helpfully for the astute listener, that because he receives so much criticism and pushback, he now protects himself from dissenting views. Because he knows his intentions are good, he surrounds himself only with people who support him. If there was ever a person at risk of hearing only what he wants to hear, it is Mark Zuckerberg.

The takeaway is that a person can be smart, well-intentioned, and sincere while also being dangerously wrong. Relying on your good intentions to confirm the validity of your actions is risky indeed.

One way to improve our chances of being wrong less often is to be humbler. When planning our initiatives, and when implementing our plans, use the pre-mortem process to identify how our plans might go awry. This includes designing processes for collecting good data, objectively reviewing that data, and adjusting course if results aren't coming in as hoped.

Doing so is no guarantee against being a fool rushing in, attempting feats the wise avoid, but it will make you more effective than most.

Be wise and be well.

Hit reply to tell me what's on your mind or write a comment directly on Klugne. If you received this post from a friend and would like to subscribe to my free weekly newsletter, click here.

Member discussion